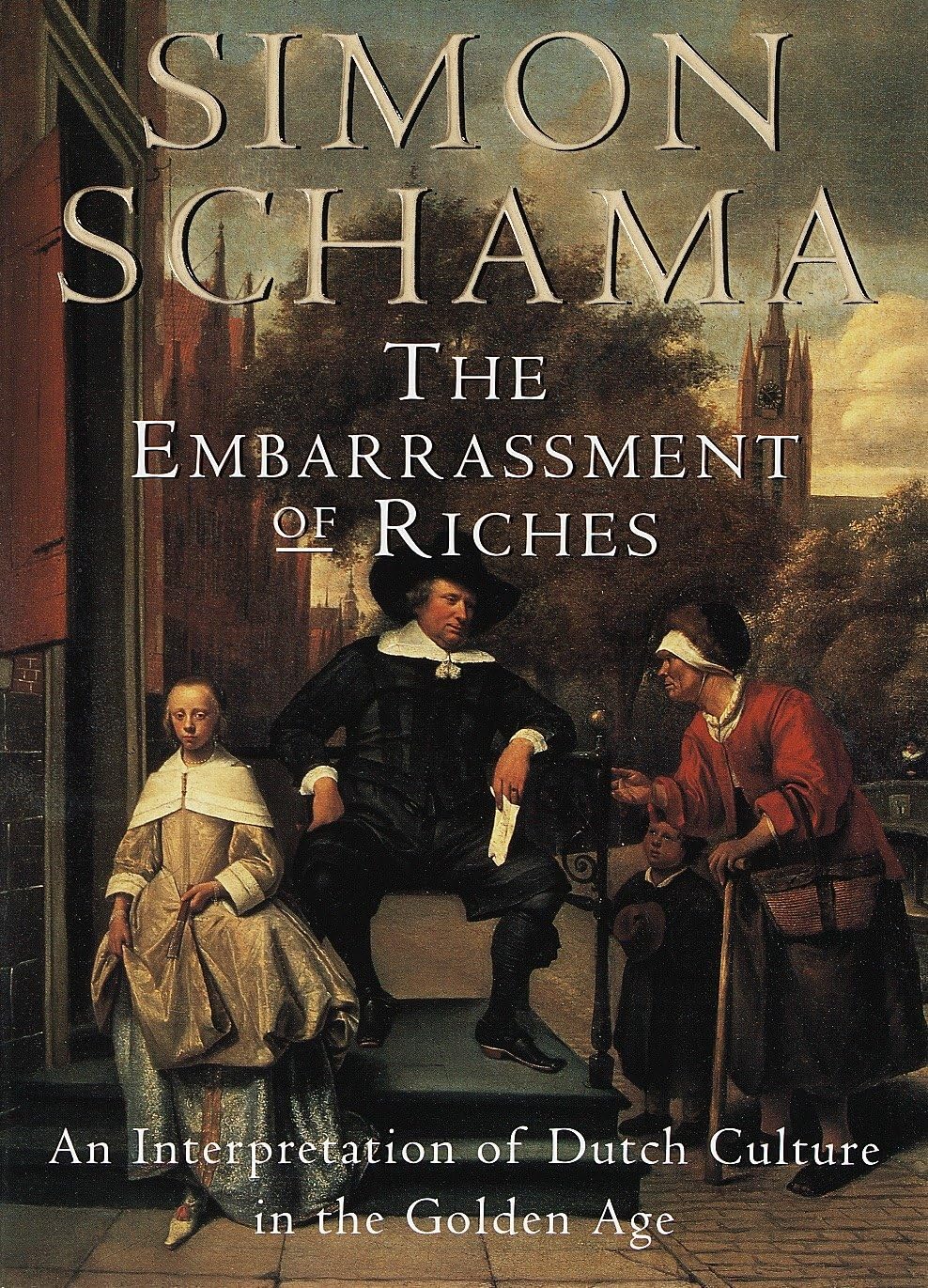

“Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution” (1989) was the first book I ever read by Simon Schama. It was sometime around 2008. I was mesmerized; I could hardly put it down. It seemed as though I had just found a new favorite historical writer, someone as graceful and penetrating as Robert Massie. I immediately began shopping for other weighty books by Schama. The first one I bought was “The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age” (1987). It is a sumptuous, layered exploration of what made the Dutch not just wealthy but profoundly distinctive during the seventeenth century. It is every bit as ambitious (not to mention as long) as Citizens, but not nearly as riveting. In short, I found it just as difficult to pick up Embarrassment of Riches, as I found it hard to put Citizens down.

In this sweeping cultural history, Schama invites us into the crowded interiors of Dutch homes, the bustling markets, and the tense moral imagination of a people who found themselves, quite suddenly, masters of a global commercial empire. Rather than tracing straightforward political triumphs or economic charts, Schama is after something subtler: how the Dutch understood themselves, their wealth, and the temptations and anxieties that accompanied their sudden rise.

At the heart of the book is Schama’s contention that the Dutch Golden Age was not simply an era of confident expansion and dazzling prosperity, but also one riddled with disquiet – an embarrassment in both senses of the word. Wealth poured into the Republic from trade in spices, sugar, slaves, and an astonishing range of global commodities. Amsterdam became the financial clearinghouse of Europe, its ports crowded with ships and its counting houses brimming with bullion and specie. Yet this very success troubled the Dutch deeply. Calvinist moral strictures and a long history of frugality clashed with the temptations of newfound luxury. The Dutch fretted that their riches might undermine the sober virtues – thrift, modesty, communal solidarity – that they believed had earned them God’s favor and secured their independence from Spain.

Schama demonstrates how this tension played out in everyday life. He spends pages on the symbolism of still-life paintings, laden with ripe fruit, expensive glassware, and delicately peeled lemons – a reminder of transience and moral fragility. He describes the obsession with cleanliness and order, down to the meticulous scrubbing of stoops and polishing of brass. Dutch houses became little theaters of moral instruction, where domestic discipline stood in for national character. The famed portraits by Rembrandt or Frans Hals, with their sober black clothing and restrained poses, likewise communicated a self-conscious morality, even as the sitters accumulated fortunes that might have scandalized their ancestors.

Schama argues persuasively that this moral anxiety was not incidental but central to Dutch identity. Unlike many European courts that openly embraced magnificence as a sign of power, the Dutch merchant elite maintained a rhetoric of simplicity and godly humility, even as they indulged in luxuries behind closed doors. The resulting culture was layered with paradox: fiercely proud of material success yet haunted by the fear that success itself might bring divine retribution.

Another theme Schama pursues is the Dutch obsession with water – at once their greatest ally and their most persistent threat. The Dutch had literally built their country from marsh and sea, wresting farmland and cities from the encroaching waters through dikes and drainage. This constant battle against floods became a metaphor for vigilance, collective effort, and divine testing. Festivals that marked victories over water disasters and the elaborate pageantry of civic guard ceremonies tied local pride to a shared narrative of struggle and resilience. Water, in Schama’s telling, was both a source of wealth – facilitating trade and fisheries – and a lurking menace, always threatening to reclaim what had been gained.

Schama also explores how this unique blend of prosperity and moral anxiety made the Dutch republic culturally and politically significant in Europe. The Netherlands became a kind of projection screen for foreign commentators. Catholic observers, especially from Spain and France, often saw the Dutch as vulgar, grasping, and obsessed with money – proof, to them, of the spiritual dangers of Protestant rebellion and commercial liberty. Meanwhile, Enlightenment thinkers and later liberals would idealize the Dutch as pioneers of toleration and civic freedom, pointing to their relative openness to religious minorities, bustling press, and thriving republican institutions.

Yet Schama is careful not to flatten this complex society into a caricature of liberal modernity. Dutch toleration, he notes, was often pragmatic and precarious, more a matter of keeping the peace in a heterogeneous commercial society than a principled embrace of pluralism. The same citizens who might allow a synagogue or Catholic chapel down the street could also riot against perceived moral threats or drown in pamphlet wars over theological hair-splitting.

What makes The Embarrassment of Riches remarkable is the way Schama brings these contradictions to life through an array of sources – everything from paintings, inventories, sermons, and moral treatises, to cookbooks and children’s toys. My favorite anecdote, however, had to do with sperm whales and their giant penises.

The Dutch were fascinated with beached sperm whales, which occasionally washed up on their coasts. These events were treated almost like public festivals: crowds gathered to marvel at the sheer scale of the animals, artists produced prints to commemorate the strandings, and preachers seized on the spectacle as an opportunity for moral instruction, warning that such monstrous incidents might be signs of God’s displeasure.

Schama pays special attention to the giant penises of these whales, which were prominently displayed and sometimes even mounted on carts to be paraded through town. He points out how these “mammoth genitals” combined the erotic with the grotesque, provoking both wonder and moral unease. For the Dutch, obsessed as they were with balancing worldly pleasures and Calvinist restraint, the giant whale – and especially its sexual organs – became a vivid, almost comic symbol of excess, lust, and the precariousness of moral discipline.

It’s a classic Schama moment: he uses this bizarre cultural episode to illuminate deeper Dutch anxieties about wealth, indulgence, and divine judgment. The spectacle of the whale’s monstrous genitals fit perfectly into a culture that was simultaneously reveling in abundance and nervously scanning for signs that their prosperity might be about to provoke ruin.

Schama’s narrative is not just long (700 pages not including end notes); it’s also often excessive and digressive, mirroring the cluttered wealth of a Dutch interior itself. Some critics have found the book too rich, teeming with anecdotes and interpretations, but this density is part of its argument, I suppose. Dutch culture, Schama suggests, was itself a crowded cabinet of curiosities, anxiously arranged to keep deeper fears at bay.

In the end, Schama offers more than a history of the Dutch Golden Age. He gives us a meditation on how societies come to terms with sudden prosperity – how they seek to balance pleasure and restraint, pride and humility, security and vigilance. The Dutch were important not only because they briefly sat atop the world economy, but because their struggle to reconcile virtue with abundance is a dilemma that continues to echo in modern capitalist cultures.

Leave a comment