The paperback edition of “The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty” was eagerly anticipated. Well, by me, at least. I have spent the past year reading broadly on the topic of economic development. Sachs’s 2005 bestseller, “The End of Poverty,” is by far the most optimistic and prescriptive of the lot. He declared triumphantly in that book: “The wealth of the rich world, the power of today’s vast storehouses of knowledge, and the declining fraction of the world that needs help to escape poverty all make the end of poverty a realistic possibility by the year 2025.” After serving a year on the ground as an economic development officer in Kandahar, Afghanistan in 2010, I’m skeptical of such sweeping and confident assertions concerning development. Nevertheless, I admired Sachs for the courage of his convictions.

According to her own account, author Nina Munk came to this project with an objective, open mind; if anything, she genuinely wanted to believe in the feasibility of Sachs’s grand and noble vision of eradicating poverty in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond. After six years researching this book, however, Munk is no fan of Jeffrey Sachs. In fact, I’m fairly confident she grew to loathe the man. By the end of the book, she dismissively refers to his many op-ed pieces in prominent publications as “jeremiads,” his rapid-fire Twitter feed as embarrassing “screeds,” the man once tenured as a Harvard economics professor at the ridiculously tender age of 28 as a “sawed-off shotgun, scattering ammunition in all directions.”

Sachs is a controversial a character; his own book makes that clear. There are only two types of people in the world, according to “The End of Povery”: smart, noble people who agree with and unquestioningly offer their enthusiastic support to Jeffrey Sachs, and ignorant, unprofessional, and painfully misguided buffoons who do not. One of the main themes in “The Idealist” is that Sachs simply does not tolerate dissent, no matter how honestly and innocently voiced. “In effect,” Munk writes, Sachs demands that you “trust him, to accept without question his approach to ending poverty, to participate in a kind of collective magical thinking.” Any criticism or questioning of his vision or approach is reliably met with “…his usual impatience and blind faith,” often ending in cruelly directed scorn and humiliating name-calling, Or, as Munk describes it in one of her rare charitable moments toward the subject of her book: “It’s never easy to disagree with Jeffrey Sachs.”

One of the things I like and respect about Sachs is that he brings an entrepreneur’s vision and passion for the cause of poverty alleviation. I’ve lived and worked in Silicon Valley for 15 years and have observed that many legendary tech entrepreneurs (Gates, Jobs, Bezos, Musk, etc.) are famously prickly and impatient with those who fail to see the future that is so clearly visible to them. For these forward thinkers, arguably the genuine geniuses amongst us, “all seems impossible until it becomes inevitable.” They live a different world where “no idea is too far fetched,” which is how Munk describes Sachs.

Not too surprisingly, Sachs’s strident criticism of economic-development-business-as-usual has been met with hostility from those who work in that system. Julie McLaughlin, the World Bank’s lead health specialist for Africa, echoes a common sentiment about Sachs, as quoted by Munk in “The Idealist”: “Jeff’s a televangelist, which seems to go over with some people, but I don’t find him all that articulate or charming. I don’t want to be lectured to.” Ah, yes, the lecturing. That’s how most development professionals unfavorably view Sachs’s approach to debate according to the author. “I don’t want to argue with you, Jeff, because I don’t want to be called ignorant or unprofessional,” one development professional is quoted as saying to Sachs in a crowded room after he delivered one of his predictably condescending, didactic, and undiplomatic public speeches on all that is wrong with development work in Africa. “I have worked in Africa for thirty years. My colleagues combined have worked in the field for one hundred plus years. We don’t like your tone. We don’t like you preaching to us. We are not your students. We do not work for you.” The bitterness and (I dare say) hate drip off every sentence. These people – the professionals at USAID, The World Bank, DFID, etc. – have developed a visceral hatred for Jeffrey Sachs. It’s a bug that Nina Munk evidently contracted during her six years on the job.

But what really “Hath Sachs Wrought?” He boldly defined a plan to eradicate poverty in the most depressed regions of the world. His ambitious goal: to help get these god-forsaken communities at least onto the first rung of the economic development ladder. His tireless evangelism funded the first phase of his vision to the tune of $120M, most of it from liberal philanthropist George Soros. Sachs’s narrative ensured that outside economic support was only temporary. Once the combined basics of clean water, healthcare, malaria-preventing bed nets, transportation networks and so on were provided for, the local population would pull themselves up by their bootstraps and carry themselves out of poverty and into the twenty-first century as self-sufficient and innovative market capitalists. For many experienced sub-Saharan Africa development practitioners, it all sounded hopelessly naïve, almost farcical. But, again, my view is (and was): why not give it a try? In 2008, I was director of corporate development at Intuit when we paid $170M for Mint.com, an online personal financial management solution that was barely earning $1M a year. The price tag of $120M to test Sachs’s ambitious proposal to eradicate poverty felt shamefully modest.

And that’s where this book left me wanting, perhaps because it’s still too early to tell. The author focuses on only two of Sachs’s model “Millennium Development Villages,” one in the badlands of northeastern Kenya, on the parched and lawless border with Somalia, and the other deep in the heart of rural Uganda. Both have experienced mixed results. On the one hand, the self-sufficiency that Sachs predicted was not irrefutably taking hold. On the other hand, pumping millions of dollars into these remote and miserably poor communities obviously had a positive impact: malaria rates were down dramatically; as was infant mortality; more people than ever had corrugated tin roofs over their homes, the African equivalent of a television in every house and two cars in the driveway. But how much of this superficial success is sustainable? Once Sachs and his dollar-rich foundation move on, will these villages be any better off ten or twenty years down the road?

The author’s mind is evidently made up. She dismisses even the early success of the project as illusionary. “By 2010 the Millennium Villages Project had become a cumbersome bureaucracy with hundreds of dependent employees,” she writes. “One hundred twenty million dollars and Sachs’s reputation were riding on the outcome of this social experiment in Africa. Was anyone prepared to smash the glass and pull the emergency cord?” But is it really necessary to pull the emergency cord just now, especially given the price tag for Phase 2? When you consider that top hedge fund managers earn over $1 billion (yes, billion) annually, is asking for another $100M that absurd? I realize that Sachs is a polarizing figure. In fact, I’m not particularly predisposed to like him; I’d rather kick him in the shins if I could, to tell the truth. But I’m not convinced that Sachs’s pie-in-the-sky vision has been fully discredited, at least not after reading “The Idealist,” which most certainly sought to discredit the man and his vision. Munk declares unequivocally that Sachs “…misjudged the complex, shifting realities in the villages. Africa is not a laboratory; Africa is chaotic and messy and unpredictable.” I’m 70% confident that she’s correct, although she didn’t make her case nearly as airtight as she evidently thinks she did. The most damning evidence of Sachs’s ill will presented by Munk is that he dismissed the assistance of celebrated MIT economist Esther Duflo to rigorously test the effects of intervention in the MVPs. Sachs evidently rejected such help because it treated global poverty alleviation like “testing pills.” It’s a shame that Sachs isn’t more open to a rigorous and scientific approach to testing his results.

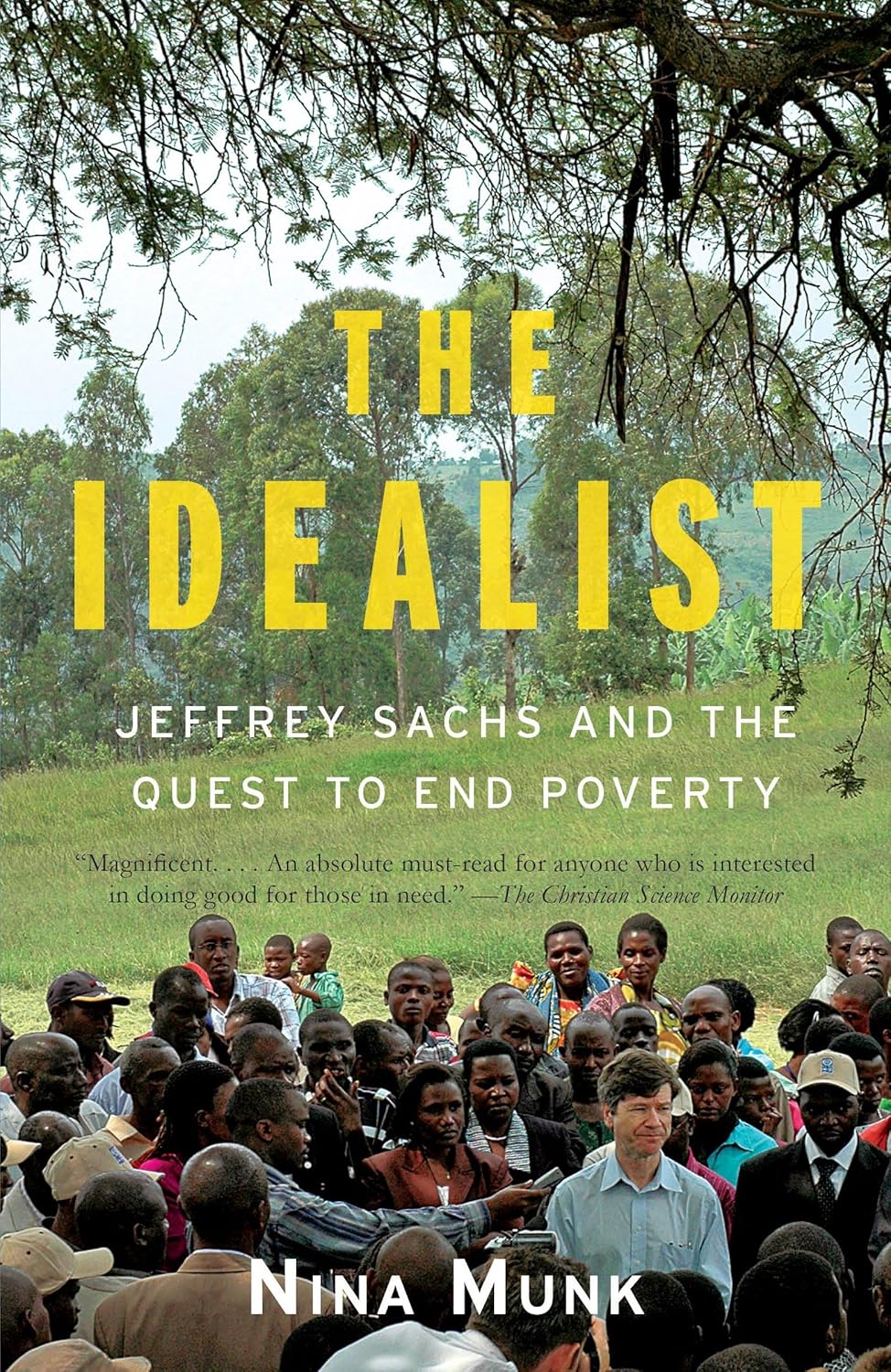

I put this book down feeling even more depressed about the fate of sub-Saharan Africa than when I started, which was pretty depressed. The cover photo in the paperback edition shows Sachs surrounded by African villagers. It’s a photo well selected by Munk and her editors as it captures perfectly the mix of Sachs’s arrogance and ridiculousness that Munk conveys in this book. I just sincerely hope that she isn’t nearly as accurate as believes that she is.

Leave a comment