Few consumer brands are more iconic and deeply woven into American culture than the Hershey Bar and M&Ms. For most Americans, these candies are more than just sweet treats—they are childhood staples, lifelong companions, and comfort foods that evoke nostalgia. Personally, my confectionery loyalty lies with Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, but the story behind these beloved products is far richer and more complex than colorful wrappers and catchy jingles might suggest.

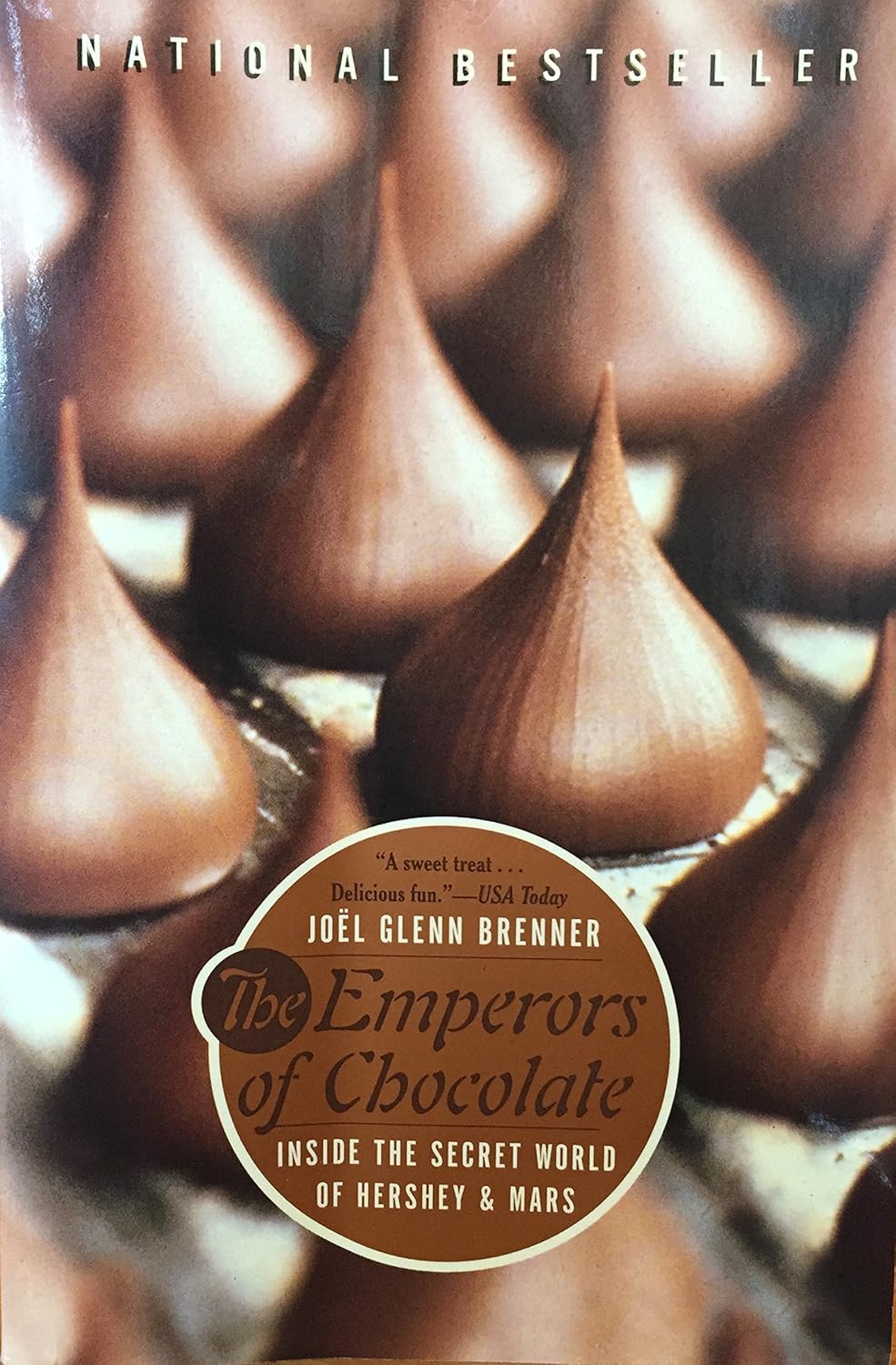

Joel Glenn Brenner’s best-selling The Emperors of Chocolate reveals that the global candy industry is a fiercely competitive—and often ruthlessly cutthroat—market rivaling the intensity of the automotive, semiconductor, or soft drink sectors. In the United States, this market is dominated by two behemoths: Hershey and Mars, companies whose histories and corporate cultures couldn’t be more diametrically opposed. It’s this interplay of familiar, beloved products and the gripping human stories behind them that makes Brenner’s book so intriguing and rewarding on multiple levels.

Although Brenner never explicitly frames it this way, the rivalry between Hershey and Mars could be viewed metaphorically as “good versus evil” or perhaps more playfully, “sweet versus sour.” Milton Hershey, the driven entrepreneurial son of a troubled Mennonite family in Pennsylvania, emerges as the embodiment of benevolence and idealism. Brenner paints Hershey as a real-life Willy Wonka figure—a visionary whose ambition extended beyond profit to creating a better world. Hershey’s creation of the model town that bears his name stands as a rare and remarkable example of an industrial utopia succeeding where others, like Robert Owen’s New Harmony, faltered.

Far from fitting the stereotypical mold of a rapacious industrial titan, Milton Hershey led a modest lifestyle and essentially died penniless, having donated his fortune to establish a pioneering orphanage for disadvantaged children. This institution still operates today, and notably, it produced one of Hershey’s savior CEOs, William Dearden, whom Brenner credits with rescuing the company during the challenges of the 1970s and 80s.

Hershey’s genius lay less in traditional business acumen and more in creative innovation and mass market creation. One surprising revelation is that Hershey did not advertise or aggressively market its products until 1970—over six decades after introducing the iconic Kiss in 1907. Instead, the company’s genius was in “creating the market” by bringing affordable milk chocolate to the American masses via the nickel chocolate bar. This pioneering move exemplifies Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen’s concept of “new market disruption,” whereby a product creates a whole new category and customer base.

In stark contrast, Hershey’s archrival, Forrest Mars, was a man of conquest and discipline. Brenner asserts that “where Milton Hershey saw utopia, Forrest Mars saw conquest.” Mars ruled his confectionary empire with an iron fist cloaked in chocolate. His authoritarian, cult-like management style was distilled into “The Five Principles of Mars” — Quality, Responsibility, Mutuality, Efficiency, and Freedom — which executives reportedly revered with almost religious fervor, akin to the fanaticism seen during China’s Cultural Revolution with Mao’s Little Red Book.

Mars’s commitment to quality was legendary and exacting: executives were expected to personally taste test products, including Kal Kan dog food, illustrating the likely origin of the phrase “eating your own dog food.” Yet Mars’s wrath at any imperfection—no matter how minor or unavoidable—was volcanic and merciless, making the company’s workplace environment notoriously harsh. Brenner’s portrayal leads one to wonder why anyone would willingly endure working for Mars.

Unlike Hershey, who reveled in product experimentation and innovation, Mars himself reportedly lacked any personal attachment to the candies his company produced. Brenner notes that Mars was quick to diversify into other markets—such as acquiring Uncle Ben’s instant rice—and today nearly half of Mars’s revenue comes from pet food, underscoring a pragmatic, market-driven ethos rather than a passion for sweets.

Brenner also highlights the paradoxical secrecy shrouding the candy industry, especially at Mars. The company’s headquarters in McLean, Virginia, are notably close to the CIA, a fact Brenner references repeatedly—perhaps a bit heavily—to underscore the secretive, almost espionage-like atmosphere surrounding corporate operations. Whether this angle is somewhat overplayed or not, it underscores how fiercely competitive and guarded the industry truly is. Interestingly, post-publication, Mars and Hershey have both demonstrated surprising levels of transparency uncommon in other sectors: Hershey’s website, for example, openly lists dozens of executive and vice-presidential names and titles, a sharp contrast to Mars’s more guarded but still revealing disclosures.

The Emperors of Chocolate is more than a business history; it’s a human story of two companies whose personalities and philosophies reflect broader American themes of entrepreneurship, innovation, and corporate culture. After finishing the book, you may find yourself reaching for a Hershey Bar with new appreciation—or viewing M&Ms in an entirely different light.

In sum, Joel Glenn Brenner’s book is a fascinating and richly detailed exploration of an industry that touches millions daily, told through the lens of two iconic companies and the remarkable men who shaped them.

Leave a comment