A friend of mine working at the American embassy in Beijing sent me this book. It is six separate defector’s stories from North Korea, providing a glimpse into typical lives north of the 38th Parallel from the end of the Cold War, through the death of Kim Il-Sung and catastrophic famine of the late 1990s, to their maladjusted lives of freedom and abundance in South Korea in the early twenty-first century. It is fascinating, often unbelievable and creepy. The Stalinist regime is unlike any other totalitarian state of the twentieth century, save possibly Pol Pot’s Cambodia at its murderous apex. Life in North Korea, even today, resembles less a repressive police state than an insane quasi-religious cult, like a contemporary Jonestown, only with over 20 million members and possessing nuclear weapons.

Author Barbara Demick writes clearly and simply. She describes a hidden world of almost incomprehensibly forced devotion — worship really — of Kim Il-Sung and his son, Kim Jong-Il. She tells how each household is provided an official portrait of father and son and are required to display it prominently and alone on a plain white wall and clean it daily with a special piece of linen provided by the government that can only be used to dust the photo and frame. All organized religion is banned in North Korea, but the citizens of the People’s Republic are provided with their own deity and Christ-like son to worship. As Demick tells us, “Instead of marking time from the birth and death of Christ, the modern era for North Koreans would now begin in 1912 with the birth of Kim Il-Sung so that the year 1996 would now be known as Juche 84.”

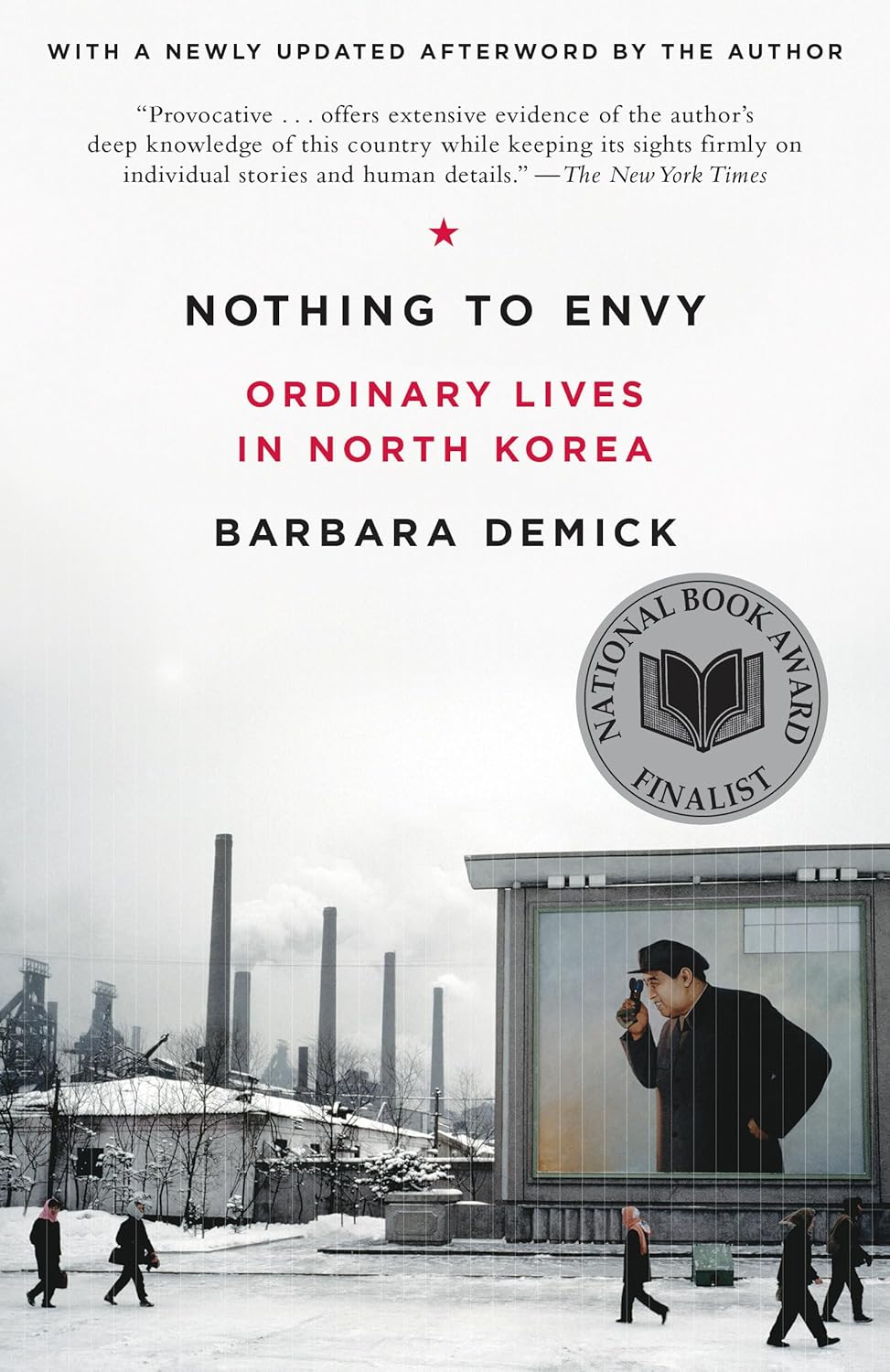

Each morning, after passing signs on the way to school declaring “Let’s eat two meals a day,” school children begin their day with a sing along to a tune called, “We Have Nothing to Envy in the World.” The official government first grade arithmetic text book provides quizzes with none too subtle political messages that are sick, but humorously absurd. For instance, “Three soldiers from the Korean People’s Army killed thirty American soldiers. How many American soldiers were killed by each of them if they killed an equal number of enemy soldiers.”

Demick charts the experience and travails of six characters representing a relative cross section of North Korean society, although they are all from the industrial northeastern coastal city of Chongjin. However, for me at least, one narrative was most compelling and memorable and insightful, the story of Mi-ran, a young woman with “tainted blood” thanks to a grandfather who served in the South Korean Army during the Korean War who suffers from lack of professional and personal opportunity in North Korea’s already economically stunted society, but nevertheless carries on a secret courtship with a promising young engineering student on the fast track to Worker’s Party membership and a life of relative privilege in Pyongyang. Her story is poignant, touching and, ultimately, uplifting.

Even if you have little interest in Korean politics, “Nothing to Envy” provides an amazing, unforgettable glimpse into perhaps the most secretive and terrifying society in history.

Leave a comment