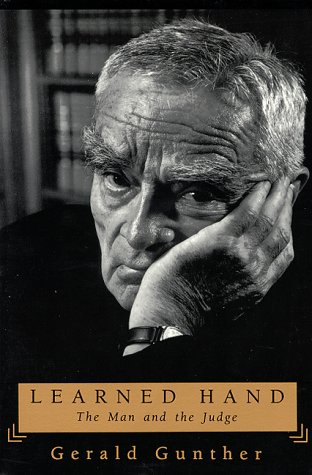

Author Gerald Gunther was one of the country’s most prominent twentieth century legal scholars. He authored the authoritative constitutional law textbook and was widely regarded as most deserving of a Supreme Court justiceship, if the criteria were purely based on merit and intellectual gravitas. Gunther clerked for Learned Hand on the Second Court of Appeals from 1953 to 1954 and played a supporting role in the McCarthy era Remington case. He went on to clerk for Chief Justice Warren the following year when Brown vs. Board of Education was decided. Thus, it is difficult to imagine a more qualified scholar to write the definitive biography on one of the twentieth century’s most influential justices, a man considered by many to be in an elite fraternity with such legal giants as Marshall, Holmes and Cardozo, despite the fact he never sat on the nation’s highest bench.

Gunther delivers a layered and textured narrative of Hand’s life. Perhaps the most important theme is Hand’s lifelong aversion to judicial activism. I learned a lot in reading this book, especially about how the due process clauses (5th and 14th amendments) have been used by both conservatives and liberals to override legislative reforms. At first, it was conservatives that leaned on the ambiguous language of the due process clauses to overturn legislation that sought to provide labor protection against overwork and unsafe conditions. Hand was firmly against judicial activism beginning in the so-called Lochner era (after the Lochner case in 1905 striking down a New York law calling for a maximum 60-hour work week in bakeries) and retained that position in the New Deal era as the conservative court sought to leverage due process arguments to negate FDR’s sweeping economic reforms. “The risk, in short, was that the Lochner philosophy allowed unelected, politically unaccountable judges to decide whether a particular legislative purpose was or was not legitimate.” For Hand, it was unconscionable that “five men [Supreme Court majority], without any reasonable probability that they are qualified for the task, determine the course of social policy for the states and the nation.”

Hand consistently resisted judicial activism via due process arguments even when liberals took that approach to successfully overturn segregation in the South, most notably with Brown vs. Board of Education. Gunther writes that “[Hand] insisted that courts were not justified in upsetting honestly reached legislative accommodations of clashing interests and values; and in the course of so doing, he even questioned Brown vs. Board of Education…that Brown constituted second-guessing of legislative choices,” although the author seeks to defend his former boss and idol as being old, tired and badgered by Felix Frankfurter to accommodate his views. There were some on the political left who felt that a double standard was acceptable (that is, generous use of the due process clauses to topple social policy was appropriate, but judges must not use the same approach to stymy economic reform legislation). Hand vigorously disagreed. “Enforcing personal rights more vigorously than property rights is an `opportunistic reversion’” he argued. As much as he might personally support liberal initiatives like the New Deal and Civil Rights, “For Hand, the notion of seeking the courts’ aid under the due-process clauses in order to protect liberal values was ultimately negated by his belief in the democratic process – the right of the people and their representatives to decide controversial issues themselves, rather than being ruled by the policy choices of an unelected, unresponsive, undemocratic judiciary.”

Hand was also a staunch defender of freedom of expression beginning with his controversial Masses decision in 1919 and proceeding with great consistency to the McCarthy era in the twilight of his career. In the Masses case Hand articulated an “incitement test” (i.e. a clear incitement to break the law as the litmus test for prohibited speech) rather than the more loosely defined “clear and present danger” as articulated by his hero, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in Schenck v. United States in 1919. According to Hand, “if the words constituted solely a counsel to violate the law, solely an instruction that it was the listener’s duty or interest to violate the law, they could be forbidden; in a democratic society, all other utterances had to be protected.” Decades later Hand’s more narrow interpretation became the law of the land, even though Hand always claimed that “[it is not] desirable for a lower court [he was then on the Second District Court of New York] to embrace the exhilarating opportunity of anticipating a doctrine which may be in the womb of time, but whose birth is distant.”

One of the things that I really loved about this book is that Gunther never neglects the human side of his subject. Many biographies tend to skip over the personal life of their subjects, instead focusing on the careers that made them memorable. Few biographies I’ve ever read place so much focus on the man as “Learned Hand.” As described by the author, Hand was a legal giant with an uncharacteristically giant case of self-doubt. His diffidence not only set him apart from his Olympian legal colleagues like Felix Frankfurther, but it also informed his judicial outlook vis-a-vis the due process clauses because he never felt so certain and right about his opinions. Hand’s “innate moderation, his capacity to perceive shades of gray, and his hostility to emotional demagoguery…” all promoted his disdain for judicial activism.

The human being that emerges from these pages is that of a tortured, nebbish man, filled with self-doubt and indecision, living in the shadow of his long dead father, and in all likelihood cuckold by his intelligent, vivacious Bryn Mar graduate wife. A man from an obscure Albany family with a long tradition at the bar, yet more-or-less a failure in his chosen profession (“I was never any good as a lawyer…I didn’t have any success, any at all,” Hand once remarked). Gunther describes a man of undeniable brilliance, yet who was almost unnaturally “risk adverse, anxiety-ridden…driven and insecure”…”with an almost masochistic penchant for self-doubt and self-criticism.” It’s not at all the image of a twentieth century American legal giant as written by one of his doting former law clerks. Indeed, Hand openly self-identified with the contemporary cartoon character Caspar Milquetoast, whose surname now has the dictionary definition of “a person who is timid or submissive.”

So how is it that the “the greatest living jurist of his time,” according to his New York Times obituary, never made it to the high court? It was a mix of unlucky politics and bad luck, according to Gunther. Failure to play party loyalist cost him professionally repeatedly. His association with Teddy Roosevelt and the short-lived progressive Bull Moose party likely cost him the Supreme Court appointment when a seat came available in 1920 as GOP leaders, especially former president and sitting Supreme Court Chief Justice William Taft, viewed him as disloyal and hostile to the 14th Amendment, then sacred to business conservative Republicans. After his engagement with the Progressive movement, Hand ducked public association with controversial political issues to preserve the neutrality of his judgeship. In 1937 FDR sought to neuter the conservative court blocking his New Deal legislation by arguing for the mandatory retirement of older judges. That politically expedient argument likely cost Hand his last opportunity to be a Justice when a vacancy arrived in 1942 as FDR would be exposed as undeniably hypocritical on the subject if he appointed Hand.

All told, this is a fantastic biography, the very best of its genre: deep, probing, honest, unflinching, and beautifully written.

Leave a comment