The early twentieth century anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski studied the yam-based culture of the Trobriand Islanders of Papua New Guinea. Villagers conspicuously displayed their yam harvest in front of their huts as a sign of wealth, but also power and prestige. At roughly the same time Norwegian-American economist Thorsten Veblen famously argued that people in the West used “conspicuous consumption” to enhance their social position. In the industrialized world of the early twenty-first century we do the same thing, only with luxury brand labels like Louis Vuitton, Gucci, and Chanel. In my humble opinion, the ostentatious display of yams and brands is equally ridiculous. Style editor Dana Thomas explores the eccentric and eye-wateringly profitable world of luxury fashion in “Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster” (2007).

The luxury goods industry is massive. It was $157 billion at the time “Deluxe” was published and has since more than doubled to $350 billion in 2023. For perspective, that’s roughly the same size of the global video game industry or all international sports leagues combined. In the beginning, in Europe in the early nineteenth century, luxury goods meant exquisite craftsmanship and quality, along with a pampered buying experience targeted to a tiny, elite clientele. All that has changed, Thomas argues. Virtually every aspect of the luxury goods industry has changed over the past quarter century (from the perspective of 2007). Luxury brand goods are now often made in a sweatshop in China with inferior quality material, sold at a sterile airport duty free shop, and targeted at thirty-year-old women on the first wrung of the career ladder. Meanwhile, tens of billions of dollars worth of counterfeited designer handbags flood street markets all over the world, further diluting brand quality. “In order to make luxury ‘accessible,’” Thomas writes, “tycoons [e.g. Bernault Arnault of LVMH] have stripped away all that has made it special. Luxury has lost its luster.”

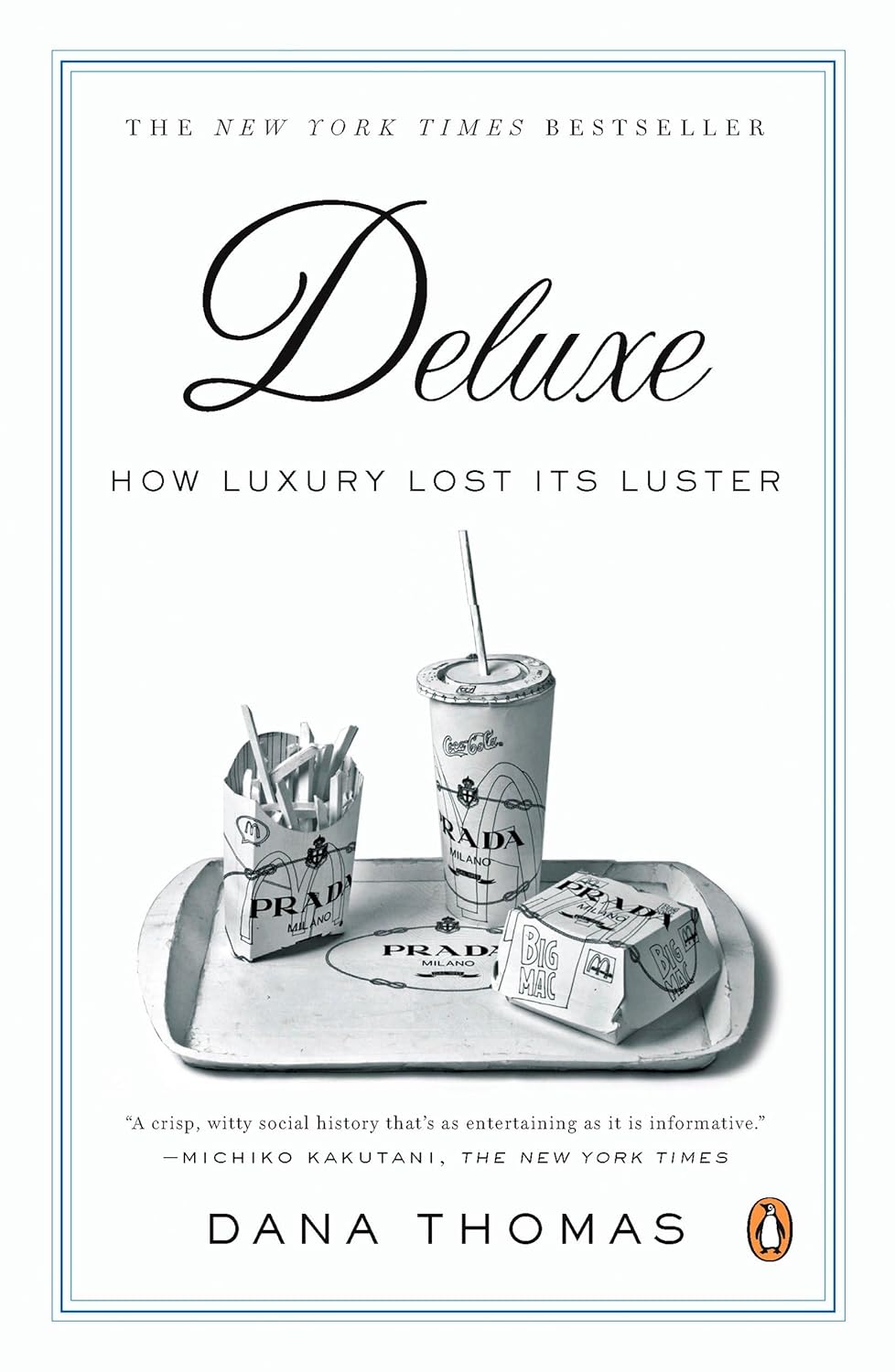

Thomas brings an interesting perspective to “Deluxe.” She’s a middle-income professional fashionista who has come to scoff at the worst offending luxury brands as though she were some old money French aristocrat. For instance, she is no fan of Louis Vuitton, the cornerstone of French luxury conglomerate LVMH. The brand accounts for almost a third of LVMH’s colossal annual revenue of $87 billion in 2023 (LVMH’s revenue was “only” $18 billion when “Deluxe” was written in 2005, a CAGR of nearly ten percent). In 1977, Louis Vuitton made just $12 million, meaning it has grown at almost 20 percent a year for half a century! With growth numbers like this, it’s hardly surprising that LVMH has been accused of mass producing luxury. Or as Thomas acidly writes: “Louis Vuitton is the McDonalds of the luxury industry.” (In fairness, the famous American designer, Tom Ford, former creative director at both Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent, sees all modern luxury as essentially fast food: “You get the same hamburger and the same experience in every McDonald’s.”)

I’m not sure the Louis Vuitton deserves the comparison to McDonalds, but both companies did revolutionize their industries. In the late 1970s, Vuitton CEO Henry Recamier, son-in-law of matriarch Renee Vuitton and a dispassionate businessman to his bones, introduced vertical integration. No longer would the luxury goods business license their brand wily-nily or allow anyone to sell their product. Henceforth the brand would have complete control over every aspect of the product experience: design, manufacturing, and distribution. It was a simple idea with a stunning impact. “In less than a decade,” Thomas writes, “Recamier had turned Louis Vuitton from a small family business that sold to an elite clientele to a powerful, publicly traded brand with substantial sales and even more potential” (sales had climbed to $143 million by 1984).

In addition to vertically integrating, the luxury industry had also “pyramidized.” At first, high fashion was all couture (i.e. bespoke and handmade). The now largely forgotten British fashion designer Charles Frederick Worth was the first to develop haute couture in the mid-nineteenth century – seasonal collections or ready-to-wear clothes carrying his signature label. All of it was original to Worth. By the 1950s the fashion industry product line had developed into a pyramid. At the top was ultra-expensive, made-to-order couture dresses for the super rich. In the middle were ready-to-wear designs targeting the middle class. At the bottom was a broad array of fragrances and accessory products that allowed less well healed customers to “buy the dream” of an elite fashion label. Eventually fragrances and handbags would carry the entire luxury industry. (I bought my wife a small bottle of Chanel No. 5 after reading Deluxe.) It was at this point that the desire to make money trumped the desire to make beautiful, high quality products.

The combination of vertical integration and growing the bottom of the fashion pyramid by expanding product lines in fragrances, shoes, wallets, and above all handbags led to explosive growth across the industry. The growth rates and margins experienced in luxury after roughly 1989 are truly astounding – and that’s coming from someone who worked in tech in Silicon Valley since 2000. For instance, Prada grew revenues from $25 million in 1991 to $750 million in 1997. That’s a mind-boggling 85% compound aggregate growth rate (CAGR) over six years. I’m not sure that even the most illustrious tech giants have equaled that. What is perhaps most noteworthy is that Thomas doesn’t seem to comprehend how unreal these numbers are nor does she try to put them into perspective.

But getting back to Louis Vuitton, Racamier embraced the pyramid, essentially invented the vertical integration model, and then correctly foresaw globalization, particularly in Asia, as luxury’s future. However, he made one catastrophic mistake: he turned to Bernault Arnault for help.

Recamier deserves a lot of credit for revitalizing the luxury brand experience, but no one person has altered the course of the industry more than Bernard Arnault, a sort of French version of Gordon Gekko. Thomas says that Arnault “collected [luxury brands] like baseball cards, displayed them like artwork, brandished them like iconography.” In the process he shifted the focus of the business from style to profitability and the product from what it is to what it represents. Arnault began as something of a corporate raider, just about the furthest thing imaginable from a fashionista. However, in the early 1980s, he acquired Christian Dior, then a neglected brand buried inside a sprawling, bankrupt French textile conglomerate. At the time of the acquisition 90 percent of Dior’s $85 million in annual revenues came from 260 licensing deals worldwide that gravely diluted the brand. Dior’s profit margin was a paltry 8 percent, almost unheard for a classic luxury brand (by 2004 Louis Vuitton’s gross margins were 80 percent). Arnault applied Recamier’s basic vertical integration to Dior: all production, distribution, and marketing would be controlled in-house.

In 1990, at age 40, Arnault triumphed over Recamier in the hostile takeover of LVMH, “one of the most venomous business takeovers” ever in France, according to the author. He applied the same strategy that worked so well for him at Dior. “If you control your factories, you control your quality,” Arnault boasted, “if you control your distribution, you control your image.” Meanwhile, he poured money into advertising, long anathem to snobbish fashion houses. By 2002 LVMH was spending over $1 billion in advertising (over 11 percent of sales at the time). Meanwhile, Arnault also hired rising stars in the fashion industry to freshen up the brands, such as luring Marc Jacobs to Vuitton to design a women’s ready-to-wear line.

However, Arnault and LVMH were out-maneuvered by the upstart designer Giorgio Armani in the critical new advertising channel of celebrity influencers. In 1988 Armani hired Wanda McDaniel to be the new “director of entertainment industry communications.” Her job was to get movie stars to wear Armani clothes in public, preferable at high visibility awards shows. Thomas says that celebrity influencers quickly emerged as “the best, and cheapest, advertising a luxury business could do.”

It’s amazing how much has changed in the global luxury market so quickly. When “Deluxe” came out in 2007 Japanese consumers utterly dominated the market. “Their impact on the business is immeasurable,” Thomas says. “Their tastes influence product and store design.” At the time, it was estimated that the Japanese purchased roughly half of all luxury goods: 20 percent were purchased in Japan and another 30 percent while traveling abroad, including custom-made duty free shopping destinations like Kalakaua Avenue in Waikiki, Hawaii, home to Chanel’s most profitable store in the world; Fred Hayman’s Giorgio Beverly Hills on Rodeo Drive; or the shopping centers at Las Vegas’s most lavish and upscale casino resorts. The most important luxury shopping venue is also perhaps the most pedestrian: Duty Free Shoppers (DFS) locations at international airports, which offer savings of up to 30 percent on luxury goods. DFS is now the world’s leading purveyor of luxury goods and, since 1996, is owned by Bernard Arnault’s LVMH, the world’s leading producer of luxury goods.

Indeed, a lot has changed in less than two decades. The Chinese are now the dominant luxury goods buying demographic globally representing almost 40 percent of the market. The Japanese have plummeted to just over 10 percent. It’s a stunning shift in market dynamics. But one thing has stayed the same, according to Thomas: the homogenization of luxury. No longer do daring designers at venerable fashion houses innovate with rule-breaking styles. Thomas says everyone now is afraid to do something too new for fear of alienating more conservative Asian customers

“Handbags are the engine that drives luxury brands today,” Thomas writes. The modern handbag was born in the early twentieth century. A fifth to a quarter of all luxury goods sales comes from handbags. The profit is over ten times the cost to make them. They don’t require sizing and the average American woman purchases more than four handbags a year. In the words of Prada chief Miuccia Prada: “The bag is the miracle of the company.” But why do women buy these overpriced bags again and again when they could just as easily have a perfectional functional and nice-looking handbag for 95 percent less? Karl Lagerfeld, the longtime creative director at Chanel, said that “[Luxury handbags] make your life more pleasant, make you dream, give you confidence, and show your neighbor you are doing well.” Even better, he says, “Everyone can afford a luxury handbag.” There’s a lot to unpack in that quote. And most of what Lagerfeld says is demonstrably false. (Can “everyone” really afford a $5,000 handbag?!) But his argument that his customers believe that luxury handbags somehow makes their lives better is probably not far off the mark, which is a sad indictment on modern culture and priorities.

Over the decades, most of the leading fashion houses have hit home runs with an innovative design that dominated the fashion scene for a season or two, or even years or decades. What started out as a statement accessory for flappers in the 1920s quickly morphed into the simple and practical necessity of the early post war era, which then morphed into something entirely different starting with the Hermes’s Kelly bag in 1953. The “it” bag had been born. Other examples include the Chanel 2.55 (1955), Gucci Jackie Bag (1961), Prada Vela backpack (1984), Hermes Birkin (1984), Dior Lady Dior (1995), and the Fendi Baguette (1997).

Thomas doesn’t say so out loud, but she clearly believes that Hermes represents everything correct with luxury fashion – fine craftsmanship, limited supply, mind boggling margins – while Louis Vuitton represents everything that’s wrong with it – focus on productivity, expansion, profitability over quality and experience. The author sizes up every interviewee with a keen and highly judgmental eye. What you wear and how you wear it goes a long way in how she perceives your worth. For instance, this is how she casually describes Gabriella Taroni, a silk manufacturer in Italy’s Como region: “When we met, Gabriella was dressed in a tight white denim dress, a black leather fur-trimmed jacket cinched with a wide belt, and a saucy pair of gold 1940s-style heels.” She introduces Kenneth Fang, a Hong Kong-based clothing manufacturer this way: “When we met, [Fang] was in a tailored hay-colored suit and cheerful cashmere vest in a pastel argyle pattern, his silver hair neatly combed back, his hands perfectly manicured.” Miuccia Prada, on the other hand, is described as an austere and evasive shrew with five years of mime training at the Piccolo Teatro and a feminist and communist, “albeit an Yves Saint Laurent wearing one.”

Luxury industry CEOs like Bernard Arnault see it as the “democratization of luxury,” but Thomas clearly sees it as diluting the value of the brand and perhaps the entire industry. “In the name of profits,” Thomas writes, “or, to put it more bluntly, greed – luxury brands [have] comprise[d] their integrity.”

Today, the once vaunted Louis Vuitton brand represents what the global luxury industry is all about, for better or worse. They’re designing their goods on computers, outsourcing production to China where labor costs are almost half, and using inferior materials for production. Thomas believes that two macro trends led inexorably to this point. The first was the democratization (read: cheapening) of luxury. The second was the tandem meteoric rise of the Chinese luxury manufacturer and consumer. In Thomas’s opinion, the convergence of these two trends – of big supply and big demand – has been “cataclysmic.” Indeed, it seems that Thomas, a one-time New York Times Style Magazine editor, now believes that haute couture fashion from the leading houses is more or less a joke. A major western advertising executive working in Shanghai described the Chinese consumer this way: “Chinese people will gladly spend a price premium for goods that are publicly consumed. But it’s like buying a big glob of shiny glitter … [They buy] to burnish their credentials as someone of the modern world by stocking up on a year’s supply of prestige.” After reading “Deluxe” it certainly feels like one would have to be a fool to spend hundreds if not thousands of dollars to buy a hyperinflated, cheaply made, shoddy designed product from Gucci, Fendi, Prada, Givenchy, and the like.

A theme of “Deluxe” is that clothing manufacturers, from The Gap to Gucci, are chasing the lowest cost and reasonably competent labor they can find. In the words of one clothing manufacturer is the improbable clothing hub of Mauritius puts it: “The textile industry has a nomadic nature and requires cheap and abundant labor.” There’s no better example than the Far East, where clothing manufacturing initially took root in Hong Kong, then migrated to mainland China, only to shift to Vietnam.

Thomas concludes “Deluxe” with this faulty analogy: “Today, the luxury industry is like Monopoly. The focus is no longer on the art of luxury; it’s on the bottom line” (the focus of Monopoly isn’t the bottom line; it’s driving all of your competition out of business). But her general point is fair: the luxury industry has several peculiarities (e.g. price increases do not necessarily come with increased product value) that make it highly unusual, but at the end of the day it’s a business just like any other, where acquiring new customers and selling them more products at more profitable prices is what it’s all about. If you’re really interested in this topic and you’re not completely turned off by four-hour-long audio programming, check out the Acquired podcast, which has in-depth and well done features on both LVMH (February 2023) and Hermes (February 2024). It’s not often one says “the podcast goes into a way more detail than the book,” but that’s true in this case.

Leave a comment