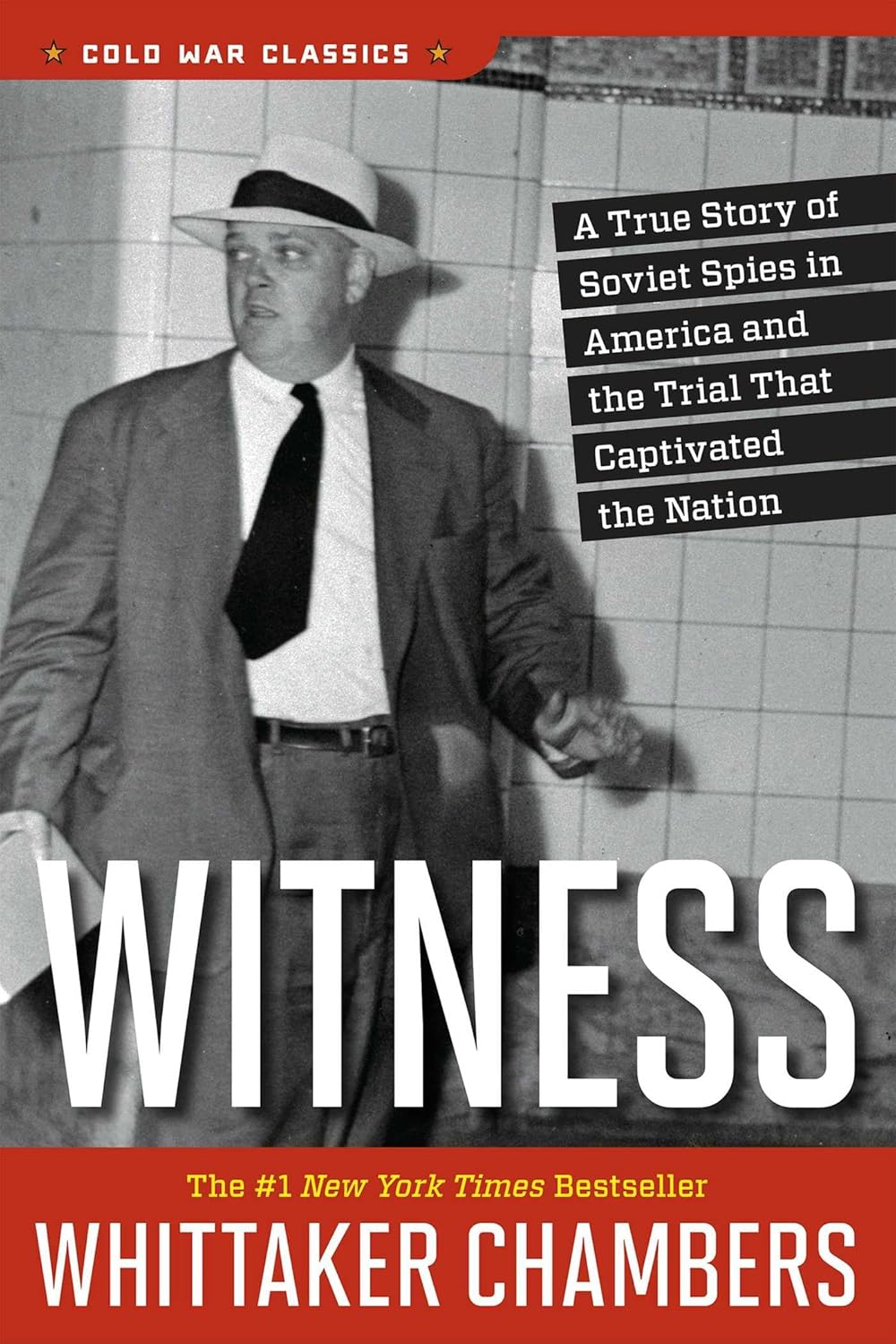

“Witness,” Whittaker Chambers’s classic autobiography, was first published in 1952 in the midst of the Red Scare known as McCarthyism. It dropped like a fifty-gallon drum of gasoline onto a bonfire.

Chambers was a former Communist operative turned state’s witness. He was raised in a fractured family living in near poverty on Long Island. After a short stint in manual labor in Washington DC and New Orleans he matriculated at Columbia University where he studied literature and his phenomenal prose talent was first discovered. It was also where he discovered the writings of Marx and Lenin, which had a profound effect on a young man in post First World War America who was convinced that Western Civilization was in existential crisis. Chambers joined the Communist Party in 1925, first serving openly in editorial positions at the “Daily Worker” and “New Masses,” and then, at the orders of the Party, in the underground, first in New York and then in Washington DC. It was in Washington that he managed the State Department’s Alger Hiss and Treasury’s Harry Dexter White as members of an undercover Communist “apparatus” that reported to Soviet Military Intelligence. Chambers describes in exquisite detail the clandestine workings of the underground and the close relationship he developed with Hiss in the mid-1930s.

Chambers would break with the Communist Party in 1938, largely over news of the purges then occurring in Russia, along with more philosophical doubts at to its moral probity. He would re-establish himself as a devout Quaker and then, somewhat miraculously, as a highly compensated senior editor at Time Magazine. In 1939, just days after the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact and the onset of the Second World War, he alerted the government of the Communist conspiracy of which he was a leader. His testimony would rather inexplicitly remain dormant for a full decade until it came to the attention of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC).

When Chambers pointed his finger at Alger Hiss, it was a political bombshell. The urbane Hiss possessed a glittering resume and top shelf social connections. Educated at Johns Hopkins and Harvard Law School, he clerked for a Supreme Court Justice and was a key participant in a wide array of monumental events of the late Second World War, including the Dumbarton Oak meeting on international peace and security, the San Francisco conference on the establishment of the United Nations, and, most ominously of all for conservatives, the Yalta Conference. By 1948 he held the prestigious post of president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Two sitting Supreme Court justices would serve as character witnesses on his behalf. Indeed, at Chambers writes, “In the persons of Alger Hiss and Harry Dexter White, the Soviet Military Intelligence sat close to the heart of the United States Government.”

Chambers’s testimony during the Hiss Case was electric; his detailed later revelations in “Witness” captivated a nation and, it may be argued, set the McCarthy era in motion. Chambers’s claims were alarmist, to say the least. “It is certain that, between the years 1930 and 1948,” he writes, “a group of almost unknown men and women, Communists or close fellow travelers, or their dupes, working in the United States Government, or in some singular unofficial relationship to it, or working in the press, affected the future of every American now alive, and indirectly the fate of every man now going into uniform [in support of the Korean War].” He goes on to say, “The danger to the nation from Communism had now grown acute, both within its own house and abroad. Its existence was threatened. And the nation did not know it.” Just two weeks after Hiss’s conviction, McCarthy would deliver his famous speech in Wheeling, West Virginia claiming he had the names of hundreds of Communists then working in the State Department. Under the present circumstances, it seemed readily believable.

“Witness” makes the Red Scare of the early 1950s much more palpable and understandable for twenty-first century American readers. The conspiracy that Chambers details in “Witness” is stunning in its scope and audacious in its aims. Today, McCarthyism and HUAC are largely seen as stains in American history, embarrassing hysteria that recklessly and needlessly ruined hundreds of innocent lives. That may be true, but reading “Witness” will present that episode of American history from a fundamentally different perspective and under a far different light. Chambers credits HUAC with administering a fair and able investigation. Congressman Richard Nixon is singled out as a particularly shrewd and observant participant. Indeed, Chambers confesses, “I liked and trusted Nixon.”

If Chambers’s testimony is to be believed – and there are no reasons not to, as far as the historical record shows – there really was a vast Communist conspiracy afoot to manipulate American foreign and domestic policy, a conspiracy that reached to the highest levels of multiple government agencies. Again, the charges Chambers makes and the evidence he advances to support it is jaw-dropping.

It helps that Chambers is a writer of genius. “Witness” has been called one of the best-written and most important autobiographies of the twentieth century – and I can see why. At nearly 700 pages in length, it is neither a short nor breezy read, but the prose is elegant and the story is utterly captivating, a monumental piece of twentieth century non-fiction.

Leave a comment