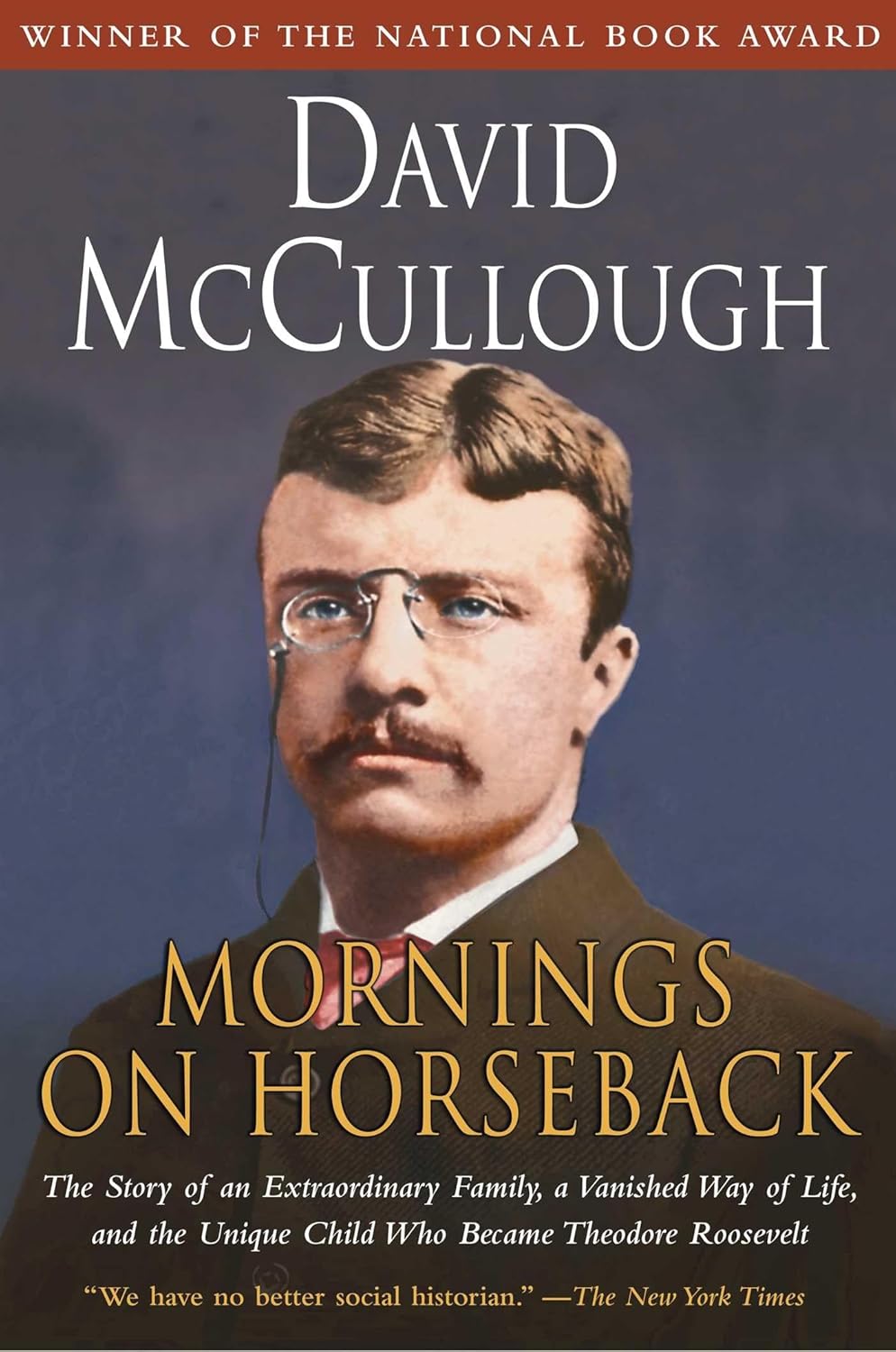

“Mornings on Horseback: The Story of an Extraordinary Family, a Vanished Way of Life and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt,” the 1982 bestseller and National Book Award-winner by David McCullough, is a wonderful book, but it’s not the family biography I expected.

Yes, the homely and crippled big sister Anna, known as “Bamie,” emerges as an unexpectedly powerful family influence and an uncommonly strong woman, especially for the late 19th century. But little brother, Elliott, so naturally gifted and yet such a disappointment in life, is given only cursory treatment. Youngest sister, Corrine, is completely forgettable. Matriarch, Martha Bulloch Roosevelt, beautiful, headstrong and, above all, very southern, is perhaps the most compelling member of the clan outside of the future president, and perhaps the strongest influence on TR’s life (McCullough writes that “[TR] was more Bulloch than a Roosevelt”), but she too seems only to flutter around the edges of the plotline. Family patriarch, Theodore Roosevelt Sr., was revered and left an indelibly positive impression on his sickly namesake, although it’s not entirely clear why. Indeed, “devotion to the memory of his father, a feeling of his father’s presence in his life, remained with him to the end,” the author claims, and it motivated TR’s very best impulses.

All of that said, I found that the narrative of “Mornings on Horseback” really turns on just a few years, from 1883 to 1886, to be exact, when TR was only in his early twenties and just finding his independent voice and recognizing his own potential. It was a brief timeframe that included some seminal events in his life: the sudden deaths of his beloved wife and mother on the same day and in the same house (February 14, 1884); the controversial GOP convention in Chicago later that year when TR tried unsuccessfully to block the nomination of George. G. Blaine; his harrowing three-year career as a ranchman in the Bad Lands of North Dakota; and, finally, his failed New York City mayoral bid in 1886, when he finished a distant third behind Democrat Abram Hewitt and the radical reformer Henry George.

McCullough basically confirms TR’s historical image as a tough-as-nails fighter, both in the literal and figurative sense. If TR lived today, he would undoubtedly be an enthusiastic member of some CrossFit gym and working on his purple belt in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. He was uncommonly courageous and indefatigable, whether pushing legislation through the statehouse in Albany or driving angry herds of cattle across a frozen Dakota plain in the dead-of-night.

Perhaps more than anything else in his early development, the Dakotas turned TR into the tough man he always wanted to be. He later wrote that “I felt great admiration for men who were fearless…and I had a great desire to be like them.” It was something he eventually achieved through sheer will power. Originally deathly afraid of everything “from grizzly bears to ‘mean’ horses and gunfighters,” he overcame it by simply pretending he wasn’t. He honed that skill by jousting with one of the more fascinating characters one will find in late nineteenth century American non-fiction: Marquis de Mores, the flamboyant, anti-Semitic French entrepreneur and adventurist (not to mention lethal dualist) who sought to disrupt the Chicago slaughterhouses by butchering the great herds right on the Plains and then shipping the meat East in refrigerated box cars. Whatever your politics today or your historical opinion of TR, he exhibited a spirit that any passionate and devoted member of society can learn from.

Perhaps ironically, the author claims that TR’s bravest and wisest decision was to accept political defeat at the 1884 convention and stay within the Republican fold. “Without question,” McCullough writes, “the Chicago convention was one of the crucial events of Theodore’s life, a dividing line with numerous consequences.” At the ridiculously tender age of 25, TR made a grand impression in his vigorous opposition to Blaine, an effort that was described by the contemporary press as “fearless,” “courageous,” “manly,” “tireless,” “plucky and unyielding,” “an earnest direct speaker, who will be listened to whenever he speaks.” Yet, in the end, he lost — and, most importantly, according to the author, somewhat graciously accepted defeat. Had he bolted the party, like many other reform-minded Republicans had, such as Seth Low, the dynamic, young and progressive mayor Brooklyn, he likely would be largely forgotten to history today.

TR has been a hero of mine since college and many of his quotes ring as true today as when he first spoke them. Perhaps none more than this gem, which is more germane today (2016), unfortunately, than ever: “While good men sit at home, not knowing that there is anything to be done, not caring to know; cultivating a feeling that politics are tiresome and dirty, and politicians vulgar bullies and bravoes; half persuaded that a republic is the contemptible rule of a mob, and secretly longing for a splendid and vigorous despotism – then remember it is not a government mastered by ignorance, it is a government betrayed by intelligence.”

Leave a comment