I took a fantastic cultural exchange trip to Cuba in November 2015. In preparation for the trip I read a variety of books about Cuba: biographies, memoirs, novels and histories. “Barardi,” by Tom Gjelten of NPR fame, was probably the single best introduction to the island’s history and contemporary affairs. The author’s central point is that “the history of Cuba can be narrated around tales of rum; it has been a symbol of Cuban life from the days of sugar and slaves through the Castro era.” And moreover, “the survival and reorganization of the Bacardi rum company following its displacement from Cuba would amount to one of the more notable tales in business history.” These theses are perhaps a bit oversold, but they make a highly readable narrative.

Cuba is (or has been) synonymous with sugar. Molasses is a byproduct of sugar production and for many years it was dumped into Cuban rivers or shipped off to New England where it was turned into rum. The Bacardis, originally from Spain, were nothing if not proud Cubans – and they were, almost to a man, great men, at least according to the author. He lionizes the family, especially founding father Emilio Facundo Bacardi. After several failed commercial endeavors and nearly destitute, the patriarch experimented with and innovated a new, light version of the local rum product from his shop in Santiago de Cuba, the main port city of eastern Cuba. Slowly, literally over decades, beginning in 1862, he and his family established a recognizable brand and built a stable business operation.

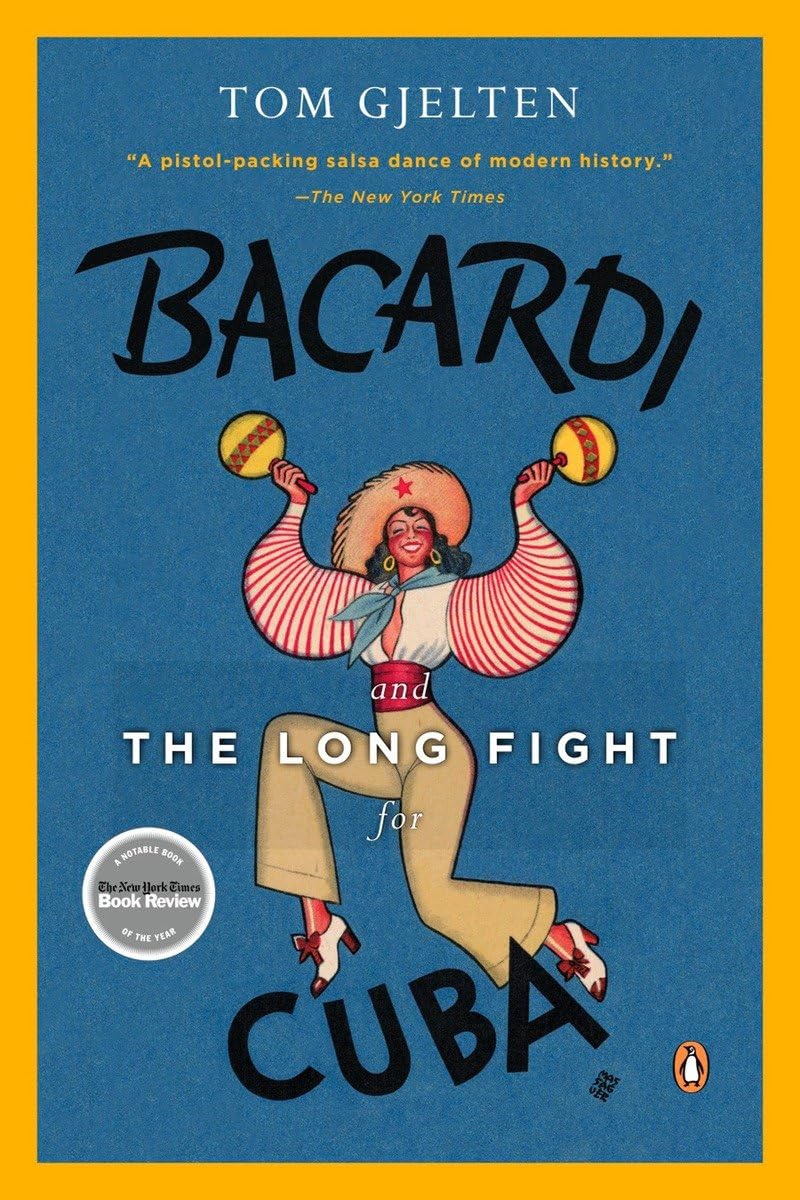

The Bacardi name – and their unusual logo, the bat – became synonymous with high quality Cuban rum. Meanwhile, the family played an outsized role in the political events that shaped Cuba in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and propelled the island’s lucrative rum industry into one of the islands most important export commodities.

To begin with, the Bacardis were, from the start and basically until the end, liberal Cuban nationalists, according to Gjelten. I found it remarkable how racially and socially diverse the Cuban revolution of 1898 really was (and that of 1868, as well). The Cubans claimed and fought for a genuinely open and free society over half-a-century before the United States adopted similar language. And the Bacardis of Santiago were consistently socially forward-leaning in these struggles, siding strongly with Cuban national heroes such as Carlos Manuel de Cespedes and Jose Marti.

The four-year American occupation after the war with Spain was a watershed period in Cuban history – and the expansion of the rum trade. The Teller and Platt Amendments may be forgotten by American students, but are well remembered by Cubans today, as I can attest from my recent travels there. The former claimed that the US had no territorial claim to Cuba, whereas the latter demanded the constitutional right to interfere in an independent Cuba to preserve stability.

The US occupation also helped popularize rum as a mix drink. The whiskey-drinking Americans found that a generous splash of Cuban rum mixed well with the Coca-Cola at the officers club, and the “Cuba Libre” was born. The mojito and daiquiri soon followed. And then U.S. Prohibition in the 1920s produced an economic boon for Cuba, for both tourism and uninhibited access to alcohol (and flesh).

Pepin Bosch, a latter Bacardi senior executive and a hero of Gjelten’s narrative, was appointed minister of finance in Carlos Prio’s government in 1950. He is described as a popular hero, loved by all. His government tenure was only 14 months, but according to the author he left the government, previously in debt, with a $14M surplus.

The conquest by Castro in 1958 is described by the author as unexpectedly sudden; a coup that succeeded mainly by “sheer audacity, irresistible energy, and political cunning.” Even more unexpected was how long lasting the revolution turned out to be. The extent to which the Cuban bourgeoisie financed Castro’s rise to power is surprising and is largely buried today under a “mutually convenient conspiracy of silence,” according to Gjelten. The Revolution is described as an ill-advised catastrophe that brought economic ruin to the island. “The Bacardi family’s Hatuey brewery in Manacas was put under the control of a pro-Castro militant whose previous job had been as a handyman at a nearby hotel.” Yet, the liberal Bacardis were smart in their contest with the new Maximum Leader. The valuable Bacardi trademarks had been spirited out of the country before the island operations were nationalized. The communists of Castro’s government evidently concentrated on the means of production, never having considered the brand value of the Bacardi name, a short-sighted failure that would end up costing the Revolution billions over the next half-century.

It is difficult to overstate how badly the collapse of the Soviet Union and global communism hurt Cuba. The Cuban economy under Castro had never been particularly strong. For instance, according to Gjelten, “By 1970, with the labor force fully employed, [Cuba] was still producing less than in had in 1958, when 31 percent of Cuban workers were jobless.” Che Guevara once commented to Gamal Nasser, “I measure the depth of the social transformation by the number of people who are affected by it and feel they have no place in the new society.” In that case, the Cuban Revolution was enormously successful. Roughly 6% of the entire population fled the island by 1970. The economy was effectively propped up by the Soviet Union. Many Cubans I met with described the 1980s as the “salad days” of the Castro Revolution. But all that changed virtually overnight. “In 1989 Cuba received about six billion dollars in aid and subsidies from socialist allies; in 1992 it received zero.” The countries total economic output shrank by at least 40% over just a handful of years in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, the Bacardi family, exiled mainly to Miami, led the charge to turn the screws even tighter on the Castro regime. It was a new and aggressive (and the author suggests myopic) approach to influencing change. “In Cuba,” Gjelten writes, “Bosch’s activism had been forward-looking and idealistic, but in exile he was more rancorous, his sense of civic duty now channeled into an angry determination to bring Castro down, by any means necessary.”

As the Cuban economy imploded, the Bacardi spirits empire boomed. A string of acquisitions (Martini & Rossi vermouth in 1992, Dewar’s whiskey and Bombay Sapphire gin in 1998, Cazadores tequila in 2002, and Grey Goose vodka in 2004) turned the old Cuban family rum business into a diversified corporate juggernaut. Therefore, the stories of Bacardi and the Revolution, in the end, could not be more different.

Leave a comment