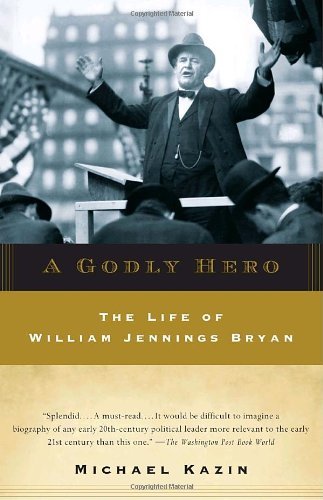

Every February or March, all across America, local Democratic Party organizations hold their annual Jefferson-Jackson Day fundraising dinner in honor of the third and seventh presidents of the United States, respectively, widely regarded as the founding fathers of the party. In 1997, President Bill Clinton helped dedicate the new, sprawling memorial to President Franklin Roosevelt on the Mall in Washington DC, the first president since Lincoln to be so honored, putting the thirty-second president on equal footing, more or less, with the signer of the Declaration of Independence, whose monument, approved by FDR in 1937, is clearly visible across the Tidal Basin. In these chosen three – Jefferson, Jackson and FDR – the modern Democratic Party have claimed their holy political trinity. However, after reading Michael Kazin’s critically acclaimed “A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan,” it is clear that the famed Nebraska orator deserves a place in that pantheon as the trailblazer of the modern Democratic Party, the man who bridged the small government, anti-federal Jefferson-Jackson party of the nineteenth century to the progressive New Deal era of the twentieth.

If William Jennings Bryan is remembered at all today, it is likely for all the wrong reasons. Either because he was three-times nominated for president (1896, 1900, 1908) by the Democratic Party and thrice defeated and/or that he led the 1925 prosecution against a Tennessee high school biology teacher for teaching the theory of evolution. As “A Godly Hero” makes abundantly clear, to summarize Bryan’s half-century career by these selective events is misleading, myopic, and supremely unfair.

Born into a relatively privileged family in southern Illinois at the start of the Civil War, William Jennings Bryan embodied the ideal politician of the age: a devout Christian, academically trained in the law, and truly brilliant in oratory. For the rest of his life the “Social Gospel” would be his political lodestar, Jesus and Jefferson his role models. “I have more than a usual power as a speaker,” Bryan recognized about himself in an early diary entry, and “God grant that I may use it wisely.” In the opinion of many contemporary Americans, particularly rural evangelical Christians in the South and West, he did.

His voice was at once mellifluous and stentorian (important in an age of open air meetings without microphones); his prose simple and direct; his arguments sincere, if not especially sophisticated. His perspective was a “… strict, populist morality based on a close reading of Scripture.” Even adversaries confessed that they had been temporarily won over after listening to him. Within months of arriving in Washington in 1891 as a freshman Congressman of no real reputation, Bryan quickly established himself as “one of his party’s most popular orators,” according to Kazin. His inimitable voice and political passion would carry him quickly to the top of his party – and eventually earn him a small fortune speaking every summer on the Chautauqua circuits. It is estimated that Bryan appeared at over six thousand scheduled speaking appearances between 1895 and 1925 (an average of two-a-day for 30 years), often to packed houses of humble citizens, many of whom traveled hours just to hear him.

Bryan’s rise to national political prominence was meteoric. During the course of just half-a-decade he went from an unknown, thirty-year-old Congressman from a remote Great Plains district in southeastern Nebraska to the presidential nominee of the oldest political party in America. And he did so on the strength of a grassroots movement built by his eloquence, sincerity, and indefatigability, not patronage or backroom wheeling-and-dealing. It was a populist playbook that served him well for decades, the only changes being the focus of his political crusade. In 1896 it was against the gold standard and in support of free silver; in 1900 it was against imperialism (although he initially supported the war against Spain and even served as a Colonel of Nebraska volunteers that never left their Florida training base); in 1908 it was against the trusts; in the late 1910s it was against alcohol; in 1925 it was against social Darwinism.

Bryan emerged as perhaps the most polarizing political figure in the country. Many critics “considered his public speaking an exercise in bathos and demagoguery.” He was loathed and feared by the urban elite, including those with long ties to the Democratic Party, and widely mistrusted by the middle class across the mid-west. “What is remarkable,” Kazin writes, “is not that Bryan lost but that he came so close to winning.”

Yet, along the way Bryan fundamentally altered the art of presidential electoral campaigning, converted his Democratic Party into the liberal wing of America’s two-party system, and according to former Wilson administration Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo, “had more to do with the shaping of the public policies [between 1895-1935] than any other American citizen,” other than those who had served as presidents.

Bryan would almost single-handedly end the long American tradition, begun by Washington, of the aloof presidential candidate who let others campaign on their behalf. Kazin argues that one of the reasons that Mark Hanna – the Karl Rove of the McKinley presidency – chose Teddy Roosevelt as a running mate in 1900 was because the young war hero and progressive reformer could somewhat match “Bryan’s combination of stump thunder and backroom sweetness…”. Meanwhile, his manager and younger brother, Charles, maintained from his offices in Lincoln one of the earliest and most extensive political marketing databases ever assembled.

It was Bryan’s extensive, vocal, and loyal grassroots following all around the country that eventually broke the grip of East Coast conservative’s control over the Democratic Party. More than anyone else, Bryan established the party as the leading liberal political organization in America. Prior to 1896, the conservative, so-called Bourbon wing of the Democratic Party was in control. Committed to laissez faire economics, small government and social conservatism, they represented their party’s classic Jefferson-Jackson heritage. These supporters of Grover Cleveland’s two non-consecutive terms as president and who had forced the uninspiring Alton Parker to the top of the 1904 Democratic ticket were buried under the combined weight of crushing electoral defeats and Bryan’s stranglehold on Southern and Western voters. He had become more than a political leader; he had become a political symbol, “a tribune of the exploited producers” of the country during a time of radical reform. Many of the political issues that he championed on the stump for years, many of which may have appeared quixotic at the turn of the century, would ultimately become law, such as a federal income tax (16th amendment), the popular election of senators (17th amendment), prohibition (18th amendment) and a women’s right to vote (19th amendment). Bryan’s extensive political influence over progressive Congressmen also played a crucial role in ensuring government control over the newly establish Federal Reserve System in 1913, another example of Bryan’s willingness to depart from the blinkered biases of his nineteenth Democratic Party forbearers. And he accomplished nearly all of this as a private citizen (Bryan’s public service was limited to only two terms in Congress [1891-1895] and 27 months as secretary of state).

So why has Bryan’s legacy been dismissed by the modern Democratic Party? First, and most likely foremost, he was an evangelical Christian who put Jesus Christ and the Social Gospel at the foundation of his political action. That alone, I believe, is enough to get many liberal academics to dilute his influence. Recent comments by sociologist George Yancey, an African-American professor and devout Christian, are illustrative: he claimed that the discrimination he’s faced in the academy for being Christian has been far worse than any racial discrimination he’s experienced, “and it hasn’t even been close.” Second, and perhaps more understandable, is Bryan’s undeniably conservative views on race. As Kazin concludes, “Bryan’s passion for democracy had always cooled at the color line.” Evidently Jefferson and Jackson’s early nineteenth century slave ownership is somehow forgivable whereas Bryan’s early twentieth century silence on Jim Crow is not.

In summary, Kazin delivers a penetrating and balanced portrait on one of the most influential politicians in American history and clearly the father of the modern Democratic Party.

Leave a comment