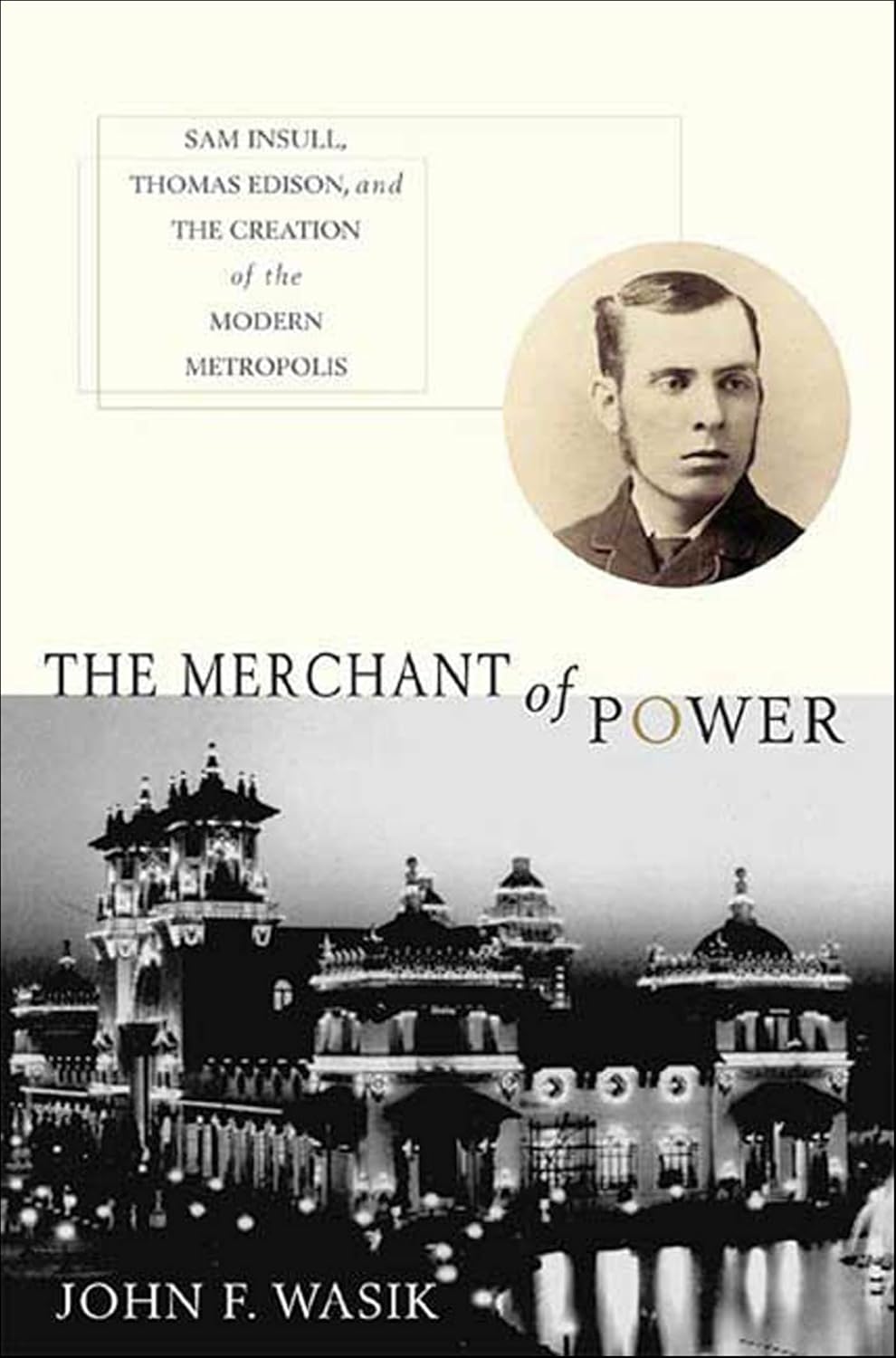

Samuel Insull is almost completely forgotten today, even in Chicago where he was once one of the most prominent and wealthiest men in the city. Few have risen so high starting from a position so low. Even fewer have crashed more swiftly, completely and spectacularly. In “The Merchant of Power: Sam Insull, Thomas Edison, and the Creation of the Modern Metropolis” (2006), John F. Wasik tells Insull’s incredible life story well, but not definitively.

Samuel Insull was a true Horatio Alger story. Born in London in 1859 to an impoverished lay preacher active in the temperance movement, he had few advantages in life and went to work at the age of 14. Just over half a century later he would control 6,000 power stations in 32 states generating 10 percent of the nation’s electricity and possess a net worth in excess of $150 million (almost $3 billion in 2024 dollars). A few years after that he would be flat broke and on the lam. If there is a more epic rags to riches to rags story than Samuel Insull, I’d love to know who it is.

Insull was a diminutive (5’3” and 120 pounds) teetotaller and a highly motivated hard worker willing to do just about anything to get ahead. Through a series of random events, Insull was offered the job of personal secretary to the legendary inventor Thomas Edison in New York City in 1881. Insull was just 22-years-old. He jumped at the opportunity and made the most of it. Before long he was Edison’s unofficial chief financial officer. What Edison needed most was capital. “It was a chronic shortage of capital that slowed the Edison combine’s unstoppable culture of innovation,” Wasik writes, and it was as a financier-entrepreneur that Insull would make his reputation and, at least for a time, his fortune.

Insull was present on September 4, 1882 when Edison’s Pearl Street power station lit up 400 light bulbs across several blocks in downtown Manhattan, including the New York Times headquarters. A few months later Edison had 231 paying customers using 3,400 light bulbs. “While the use of gas for lighting continued well into the first two decades of the twentieth century,” Wasik writes, “gas was technically obsolete.” But Thomas Edison, for all of his creative genius, was no businessman and no manager. He benefited greatly from his young British aide, who, in Edison’s opinion, “was always looking at the dollar angle.” The Edison power companies did literally everything for their customers when it came to electricity: Edison produced and sold electrical power; installed infrastructure to transport electricity from the power station to buildings; wired buildings for electricity; and then made and sold all of the light bulbs and fixtures. To make matters worse, Edison was staunchly committed to the “direct-current” (DC) model of power generation, which limited the range of power distribution to less than one mile from the power station. From a cost accounting perspective the Edison power companies were a total mess.

Edison and company attracted an important financial investor in 1881, the German-American journalist turned railroad tycoon Henry Villard. Villard would coach Insull on how to successfully complete large capital raises from banks, a skill that would turn out to be more important for his future than anything the Wizard of Menlo Park had to show him. Villard’s aim was to combine all of Edison’s interests into a single entity. He essentially bought out Edison and became president of the new company, Edison General Electric.

Insull now worked for Villard, who remained his financial mentor. Westinghouse, which embraced the vastly superior AC system, as well as a team-based approach to R&D, including the contributions of Nikola Tesla, was a formidable Edison rival. So, too, was Thomson-Houston, a company with roughly the same gross sales at Edison, but with twice the profit. In February 1892 JP Morgan orchestrated a merger between Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston to create the new General Electric Company, valued at $50 million, the second largest company in the world at the time behind only US Steel. Henry Villard was forced out of the combined company, which would be run by a Thomson-Houston executive named Charles Coffin. Insull was the only Edison executive to keep his job; Wasik says that he respected Coffin. Villard and Insull’s relationship, however, did not survive the merger. Edison, meanwhile, supported Insull unwaveringly for the rest of his life. Insull left GE shortly after the merger to take over Chicago Edison, an operation that may sound impressive, but the author claims was “a puny also-ran in a competitive market” (Chicago had 45 different power companies when Insull arrived in 1892).

Insull’s goal was simple: electrify everything. His strategy was equally simple (and perilous): win by acquiring competitors using a variety of aggressive financing instruments. Insull was in town less than a year before scooping up rival Chicago Arc Light & Power Company for $2.2 million using the issuance of debentures (unsecured loan certificate issued by a company, backed by general credit rather than specific assets) paying 6 percent interest. Insull wasn’t afraid to spend a lot of money to achieve his objectives, especially when the money mostly belonged to somebody else. One of Insull’s financial innovations was the creation of an open-ended mortgage. The bond-backed, open-ended mortgage was a highly flexible financial instrument perfectly suited to Insull’s needs. It acted like an ever-expanding line of credit with the bank that was not tied to any one expenditure. Insull used it to snap up small and rural power countries all across the midwest. In 1911 he put his sprawling collection of small utilities under the umbrella of a holding company called Middle West Utilities.

In 1897 Insull was elected president of the National Electric Light Association (NELA), a national trade association composed of local power companies. To the surprise of many, Insull used his platform at NELA to promote state regulation of the utility industry due to its natural monopolistic structure. The development of the steam-turbine plant at the turn of the century made utility power generation far more efficient and powerful, doubling the efficiency of converting heat and motion into electricity. For example, around 1900 a 3.5-megawatt plant was the most powerful in existence. By 1910 24-megawatt units were standard. Before 1920 Insull was installing 120-megawatt generators. Insull’s insatiable drive for bigger-faster-stronger plants made Chicago “the most energy-intensive place in the world,” according to Wasik. Moreover, Wasik writes that Insull was “an ambassador, salesman, and chief spokesman for the modern lifestyle” of electricity and electric homegoods. He was the PT Barnum of electrification, and actively studied the great promoters techniques. “The more ways [Insull] presented for consuming [electricity],” Wasik says, “the more electrons he could sell.” By 1910 only 16 percent of homes had electricity. Less than twenty years later almost every home in America was hooked up to the grid. The First World War was no impediment to growth. The sales of electrical appliances quadrupled in just five years, growing from $23 million in 1915 to $83 million in 1920. The same was true with factories. Only 10 percent of factories used electric motors in 1905. By the end of the 1920s it was over 80 percent. By 1925 Insull was selling over 100,000 electrical items, everything from toasters to curling irons.

Insull had a second passion in life after electricity – the opera. He loved the theater and played a major role in the management and growth of the Chicago Grand Opera. Insull’s wife, Gladys Wallis, was a famed stage actress, and his mistress, Mary Garden, “was to grand opera what Insull was to power plants,”according to the author. Insull led the effort to build the magnificent $23 million (almost half a billion dollars in today’s money), 3,500 seat Civic Opera House, also known as “Insull’s Throne.”

He was also a generous employer, Wasik says, rarely firing any employees after his many takeovers, offering a full pension to workers aged 60 with 15 years of service, and scholarships to attend night school. Wasik says these were industry-leading human resource benefits at the time. Insull’s utility stocks offered healthy tax-exempt dividends of up to 5 percent. Meanwhile, his core product literally cleaned up the cities he served: electric rail service eliminated millions of tons of noisome horse manure from the streets, while electric illumination removed the stench and stains of gas. Electric refrigerators, fans, and irons made home life much easier. Property values along his electrified rail lines shot up by a factor of eight. Electricity truly brought the good life to Chicago and beyond.

Politically, Insull was a staunch Republican and had no greater champion than president Herbert Hoover, who enthusiastically endorsed Insull’s vision of privately owned utility companies unregulated by the federal government. Insull had no greater political foe than the progressive governor of New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. FDR wanted to do more than just regulate the utility companies, he wanted to control them. He looked at the price of electricity in Canada, which had publicly owned utilities, and compared it to prices paid by New Yorkers receiving electricity from privately owned utilities and discovered that prices were over six times greater ($3.32 in Canada versus $19.95 in NYC). Inexplicably and unfortunately, Wasik never investigates this claim to determine the likely cause of the dramatic price discrepancy (i.e. monopolistic greed, pure and simple, as FDR claimed, or something else?).

Insull’s empire came crashing down in a way not dissimilar to Bernie Madoff’s a century later. The Insull utility empire was something of a house of cards. He used holding companies to buy a controlling share in local utilities. By 1930 he controlled 4,405 utility companies serving 6.3 million Americans with gross earnings of $162 million a year. He was on the board of directors of over 150 companies and earned a salary of $1.4 million ($26 million today) from 13 companies plus another $500,000 in dividends from his companies. It was a $2.5 billion empire (which Insull controlled with his $20 million stake in two investment trusts), all of it listed on the Chicago Stock Exchange. Insull himself was worth $150 million just before the Depression hit.

Insull mainly used bank loans to buy the securities. A typical holding company might be capitalized at $500 million: $250 million in bonds, $150 million in preferred (non-voting) shares, and $100 million common (voting) stock. Thus, a $50 million loan would suffice to completely control a $500 million company. That one holding company capitalized at $500 million and controlled with a $50 million bank loan might control ten operating companies with $5 billion in real assets, returning a gross profit of 7 percent or $350 million a year. But, Wasik warns, “the power of leverage [to control holding companies] works only if profits and the stock market value of the underlying stock increases.” Once security prices start to drop precipitously and consistently, as they did in the early 1930s (and 2008), and you can no longer steal from Peter to pay Paul, the whole scheme falls apart, as it eventually did for Insull (and Madoff). It was essentially unpreventable, according to Wasik: “The holding company structure…was a straw house that could not have been sustained during any economic downturn.” The complexity of the holding company system was comical. Consider this, Insull and his inner circle controlled roughly two-thirds of the two main holding companies or trusts, Corporation Securities and Insull Securities. These two holding companies owned 28 percent of the voting stock of Middle West Utilities, a mid-level holding company, which owned almost all of National Electric Power, which in turn owned 93 percent of National Public Service, which owned all of Seaboard Public Service, which owned all the assets of Georgia Power & Light. And on and on it goes. Wasik claims that the holding company structure allowed Insull to control assets of $500 million in 32 states and 5,000 communities with only $27 million invested. By 1932, just eight holding companies controlled 75 percent of the investor-owned utilities in the United States. “The holding company pyramids were nothing but legal shell games,” Wasik says, and it took the Depression to expose them for what they were.

Desperately afraid of losing control of his empire built on relatively small positions in vast holding companies, Insull went to great lengths to prop up the prices of his utility stocks to ward off takeover attempts. He became vulnerable to “greenmail” threats: when a competitor buys a large stake in your company’s stock in the hopes of selling it back to you at an inflated price. This is precisely what happened with Insull’s most aggressive opponent, Cyrus Eaton, a minister turned stock speculator from Cleveland, Ohio who sold 160,000 of Insull’s company back to him for a whopping $48 million. The value of Insull’s assets, which he had put up as collateral for previous loans, fell dramatically. Roughly 90 percent of the various holding companies’s assets were already committed as collateral against $100 million in securities; there was nowhere left to turn and the banks began withholding future loans. Insull still heavily promoted his dividend-bearing stocks in an attempt to boost the share price, a tactic that would come back to haunt him.

Wasik says that Insull’s fall was “the greatest single business failure in American history” and that “Insull symbolized everything that was repugnant about the rapacious utility barons.” There would be a silver lining to Insull’s fall, however. Wasik says that Insull’s convoluted financial empire of interlocking holding companies was directly responsible for the modern securities and utility regulations passed as part of the New Deal. Insull and his wife fled first to fascist Italy and then to Greece. Adding insult to injury, the Civic Opera, the greatest pride in Insull’s life next to his family and utilities empire, went bankrupt in January 1932. Meanwhile, Insull was formally indicted for fraud and embezzlement. He vigorously fought extradition while his old nemesis and new president, FDR, did everything he could to bring him home to face justice.

An exhausted 75-year-old Insull finally returned to Chicago in 1934 to face charges along with sixteen other co-conspirators, including his brother and son. Wasik concedes that it was a complex case featuring a mix of questionable, but not necessarily illegal, financial transactions, stock sales, accounting methods, and management decisions. At the heart of the prosecution’s case was the charge that Insull was deliberately selling “watered stocks” knowing full well that the underlying value was far less than what he claimed. Insull’s basic defense was that the Depression ruined him, plain and simple; he didn’t do anything illegal, he just got run over, just like everyone else. The fact that Insull refused to suspend dividend payments on his stock despite the obvious corporate financial crisis his companies were in was painted by the prosecution as a deliberate attempt to deceive and defraud the public. After a trial lasting weeks, Insull and the rest of his co-defendants were found not guilty after only a few minutes deliberation by the jury. However, it was a hollow victory for Samuel Insull and his family. Accustomed to the lifestyle of the obscenely rich and socially privileged, Insull was left financially ruined and socially ostracized. Even after all of his possessions had been sold off he was still almost $20 million in debt to creditors. He died in the Paris subway in July 1938.

Samuel Insull’s story is certainly an amazing (and tragic) one. I wish Wasik had spent more energy showing whether or not Insull was using his monopoly position to deliberately gouge consumers in the 1920s and 1930s and perhaps what the overall macroeconomic effect of his electrification efforts were, but overall this was a fun and informative read.

Leave a comment