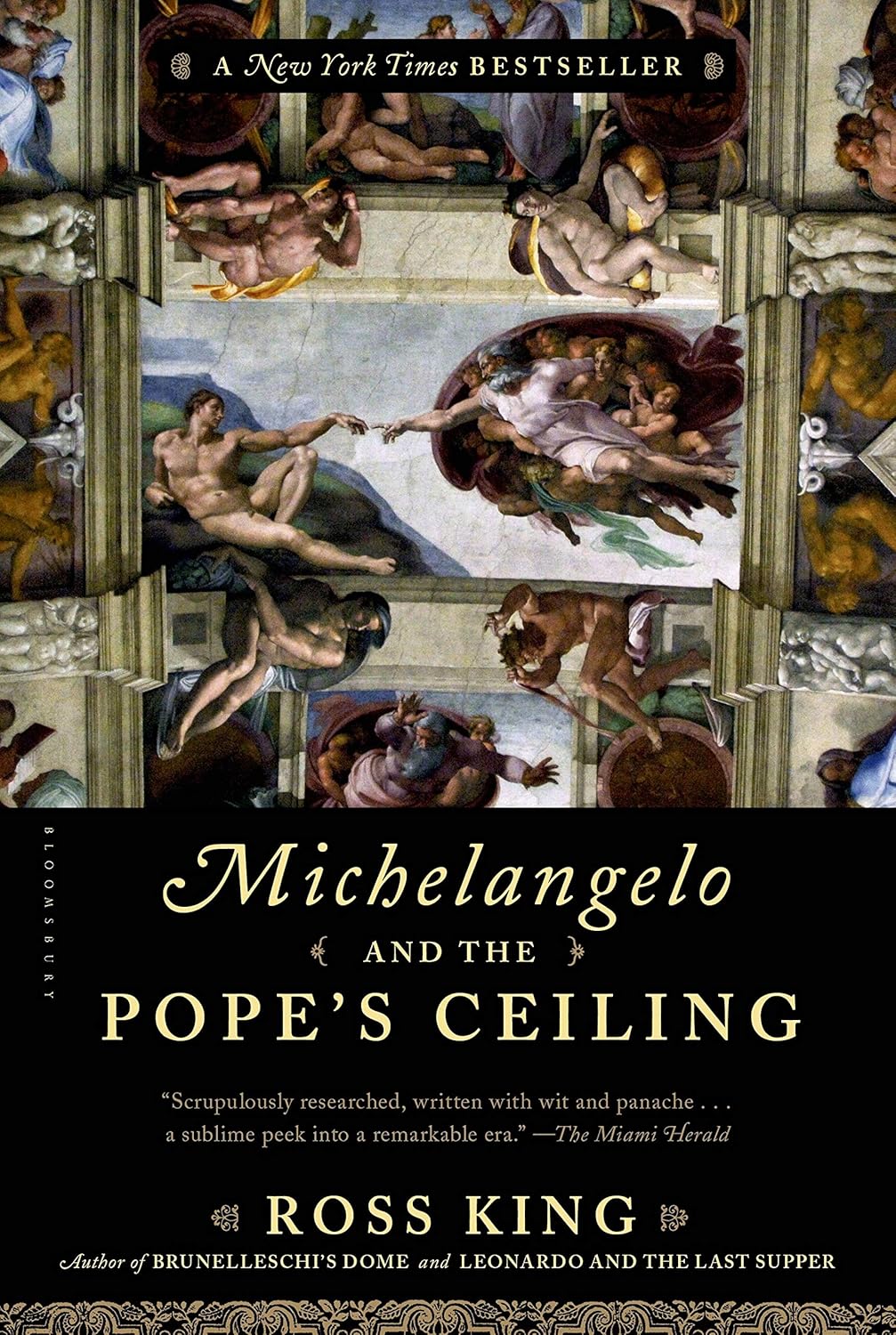

Ross King is one of the few writers who makes learning about the Italian Renaissance fun and easy. Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling (2003) tells the story of the most famous vaulted fresco on earth – Michelangelo’s painting of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling from 1508 to 1512.

Michelangelo was not an easy man to get along with. The author describes his subject as notoriously “arrogant, insolent, and impulsive,” and later portrays him as “a moody, aloof, obsessive perfectionist.” Not exactly someone you’d want to work for or with.

He is famous today for many legendary works of art. Ironically, the project that obsessed him the most and for the longest time (nearly half a century) is hardly remembered today: the tomb of Pope Julius II. Planned as a freestanding structure 34 feet long and 50 feet high featuring over forty life-sized statues, the tomb was truly breathtaking in scope. Michelangelo was to receive 1,200 ducats a year during construction (roughly ten times the average sculptor salary) plus a massive 10,000 ducat bonus upon completion. The figures and dimensions of the project broke all precedents.

But it was not to be. Just as the tomb project was getting underway, Julius was struck by an even more ambitious endeavor – the demolition and reconstruction of St Peter’s Basilica. There wouldn’t be enough money to go around; compromises had to be made. Michelangelo’s dream commission was unceremoniously shelved in 1506. He was crushed and would evidently never get over the lost opportunity for such a magnificent undertaking. The author says that Michelangelo was convinced that the pope’s architect-in-chief, Donato Bramante of Urbino, had something to do with the sudden change of plans. The great Florentine artist, then thirty-one-years-old, left Rome in a huff, vowing never to return. The pope (and Bramante) wooed him back with what Michelangelo believed was an impossible task: frescoing the vault of the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo saw it as a trap. He was convinced Bramante was determined to thwart his artistic career and humiliate him with a project (ceiling painting) often delegated to assistants and in a medium (fresco) that he was unskilled at.

The Sistine Chapel was a relatively new building in 1506. Begun by Julius’s uncle, Pope Sixtus IV (reigned 1471 to 1484), the chapel was built to the exact dimensions of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem as given by the Bible. That is, twice as long as it is high, and three times as long as it is wide (130 feet long X 43 feet wide X 65 feet high). The chapel was intended to be a private place of worship for the highest ranking members of the Catholic hierarchy and, in the event of invasion or mob violence, a fortified place of refuge. The chapel officially opened in the summer of 1483. In 1504, shifting of the foundation caused ominous cracks to appear in the vaulted ceiling. Michelangelo was thus brought in to refurbish and repaint the damaged ceiling, which originally featured a simple starry night pattern painted by Piero Matteo d’Amelia.

By the early sixteenth century, Michelangelo’s gifts as a sculptor were widely recognized. He was not, however, considered a great painter, let alone a frescoist, the difficult art of applying pigment to a wet plaster surface. The plaster would dry in less than eight hours, meaning every day the fresco artist was racing against the clock. Each day’s work – or “giornata” in Italian – covered an area between 15 and 30 square feet. “The art of fresco enjoyed such esteem precisely because it was so famously difficult to master,” King says. (Cimabue’s use of fresco in the basilica in Assisi in 1280 and his student Giotto’s fresco cycles at the Arena Chapel in Padua in 1305 are often considered the start of the Renaissance.) Moreover, Michelangelo had no skill in the tricky technique of creating illusionistic effects on high, curved surfaces, which was critical for fresco painting. Finally, King writes that ceiling and vault paintings had usually been reserved for assistants or lesser-known artists. Major artistic talent – such as Botticelli, Perugino, Ghirlandaio, and Roselli – frescoed the walls of the chapel between 1481 and 1483, not the ceiling.

Michelangelo maintained a frosty relationship with his patron, Pope Julius II, who was not the kind of man one would want to maintain a frosty relationship with. The author says, “No pope before or since has enjoyed such a fearsome reputation.” However, Michelangelo possessed one critical ally and protector in Rome: Francesco Alidosi, cardinal of Pavia – and Julius’s closest and most trusted advisor. Alidosi is the one who wrote up Michelangelo’s contract (now lost) for painting the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo was to be paid 3,000 ducats for the project, a very generous but not outlandish sum when considering the artist was responsible for acquiring all of his pigments (only 25 ducats because he avoided expensive pigments like ultramarine) and brushes, pay his assistants (who he hated, but desperately needed), and even construct the highly unusual scaffolding required to paint the ceiling while not interfering with religious services below. Artists in 1508 were much like any other skilled craftsman, and just like the stonemason or goldsmith, Michelangelo could expect to receive very specific instruction from his demanding and ambitious patron, who wanted to return Rome to its glory days. In addition, King says that the planned scenes from the Old Testament on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel were deeply influenced by Sienese sculptor Jacopo della Quercia’s Porta Magna (Great Door) of the church of San Petronio in Bologna and Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Doors of Paradise for the Baptistry of Florence.

Genesis was a worthy subject for Michelangelo’s artistic genius. King says that he had no use for any sort of placid landscape painting, which were then just coming into fashion. Rather, he was fascinated by “tragic, violent narratives of crime and punishment” and was especially influenced by the apocalyptic vision of the recently executed Dominican monk Savonarola. Biblical scenes like the Great Flood lent themselves to his unique style of crafting muscular, heroic, yet life-like nudes in various forms of strenuous, but graceful exertion. Michelangelo was “the high priest of idealized masculine beauty,” King crows. He demonstrated this famously with his cartoon for the never completed fresco of the Battle of Cascina (actually a minor skirmish with the Pisans in 1364) that was planned for the walls of the Palazzo della Signoria (Hall of the Great Council) in Florence in 1505. Almost simultaneously the ancient statue of the Trojan priest Laocoon, likely sculpted around 25 BC on the island of Rhodes, was unearthed in a vineyard on the Esquiline Hill in Rome. It showed Laocoon and his two sons, all of them nude, wrestling valiantly with a sea serpent in poses that are both classical and Michelangelian. The deliberate referencing of poses, motifs, and stylistic details from earlier works of art, which Michelangelo clearly did, is known as “quoting,” and was not considered copying or plagiaristic, but rather a mark of erudition and artistic style. A notable exception to this theme are the 91 ancestors of Christ (including 25 women) he painted in the Sistine Chapel, nearly all of whom are depicted doing the activities of everyday life, such as cutting cloth or tending to children, a rarity in the oeuvre of Michelangelo.

Michelangelo was also daringly original, often in ways lost on contemporary observers because his art has been so influential in our understanding of things. For instance, Michelangelo’s depiction of God and the creation of man were mostly original to him. The figure of God as an old man with a beard and wearing a robe is strongly influenced by ancient depictions of Zeus and Jupiter, and was not familiar to sixteenth century Europeans. Moreover, Genesis 2:7 clearly explains that God created Adam from dust and then gave him life by breathing into his nostrils, not touching fingertips, as imagined and immortalized by Michelangelo.

Just as Michelangelo was getting started on the Sistine Chapel, a precociously talented young (25 years old, and 8 years younger than Michelangelo) artist named Raphael arrived in Rome in 1508. Raphael was many things that Michelangelo was not: handsome, easy-going, civilized, well-groomed, virile and – perhaps most importantly – liked and supported by Donato Bramante. The young painter from Bramante’s hometown of Urbino was invited to Rome as one of a collection of talented artists to decorate the room that came to be called the Stanza della Segnatura, which Julius planned to be his personal library. The other, more established artists were soon jettisoned from the project, their half-completed frescoes scraped from the walls to make room for the work of the incomparable Raphael. Many consider his four frescoes the peak of High Renaissance art: The School of Athens (depicting philosophers), The Dispute of the Holy Sacrament or Disputa (theologians), The Parnassus (poets), and The Cardinal Virtues and the Law (female personification of the cardinal virtues of prudence, temperance, and fortitude). All were completed between 1508 and 1511.

King makes much of the rivalry between Michelangelo and Raphael, with the latter mostly coming out on top, at least initially. Michelangelo saw the gifted Raphael as no more than “an envious and malicious imitator” in league with the hated Bramante, according to the author. “Michelangelo was the one person in Rome on whom Raphael’s famous charm was lost,” he says. Raphael’s work in the Stanza della Segnatura was brisk and uniformly brilliant; Michelangelo’s early work in the Sistine Chapel was a plodding (Giorgio Vasari claims that the pope literally beat him with a stick because of his slow progress) and rather choppy performance, with significant changes in style and technique as he learned from his initial errors in the large-scale compositions of The Flood and The Drunkenness of Noah. (For instance, the prophets painted in the second half of the chapel are, on average, four feet taller than those painted in the first.)

Whereas the figures in Raphael’s “Disputa” are “lively” and “fluent,” in the author’s assessment, those in Michelangelo’s “Noah” are “stiff and solid.” King goes on to argue that Raphael’s Vatican frescoes represented the apotheosis of a style of art that had been developing over the past few decades from such notable late quatrocento artists as Perugino, Ghirlandaio, and Leonardo. But Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel “marked an entirely new direction,” according to the author. Michelangelo had somehow brought the power and energy and vitality of his sculptures to the realm of painting.

King compares the difference in style between Raphael and Michelangelo to Edmund Burke’s 1752 distinction between the beautiful and the sublime: Raphael’s Stanza dells Stegnatura was beautiful (i.e. smooth, delicate, and elegant) whereas Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel was sublime (i.e. powerful, rugged, and vast). “There was no higher goal for an artist during the Renaissance than to make his figures seem alive,” King says, and no one did that better than Michelangelo.

But not everyone was impressed. The great theologian Erasmus visited Rome in 1509 when Michelangelo and Raphael were busy at work at the Vatican. He was disappointed with what he saw, almost embarrassed even. His rapid composition of “The Praise of Folly” over seven days on his return from Rome was largely aimed at the culture of the Holy City under Julius and his cardinals. Erasmus saw in the “warrior pope” not the coming of a second golden age of Rome, but rather “a drunken, impious, pederastic braggart bent only on war, corruption, and personal glory,” as he would later write in “Julius Excluded from Heaven” (1517).

King credits Raphael with being a master of space and character composition. His famous School of Athens included many of the leading artists of the High Renaissance as characters in his fresco – Leonardo as Plato, Perugino as Socrates, Bramante as Euclid, and himself as either Ptolemy or Apelles (it’s disputed). Raphael added Michelangelo to the fresco later after viewing and being deeply impressed by the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo was depicted as Heraclitus, a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher known for his doctrine of change and becoming (e.g. “No man ever steps in the same river twice”), and also notorious for possessing a bad temper and bitter scorn for his rivals.

Michelangelo suffered from two major distractions during his four year stay in Rome working on the Sistine Chapel. The first was his family. He had four brothers and a father back in Florence, and all but one of them was an underachieving nuisance in steady need of money. A second noteworthy theme of the book is the constant intrusion of geo-political events and Julius’s aggressive foreign policy during his decadelong (1503-1513) pontificate. The affairs of the papal states were one of ceaseless unrest and turmoil, which had a direct impact on the pope’s artistic ambitions for the Vatican and Rome in general because it both distracted his attention and diverted his resources. The situation was made even more awkward for Michelangelo as his native Florence had a republican government led by Piero Soderini, which reliably supported Julius’s archnemesis, the French monarch Louis XII. In some cases, Julius’s foreign affairs had a direct impact on the artwork he commissioned. For instance, in 1512 Raphael completed “The Expulsion of Heliodorus.” In the Bible, Heliodorus was a high-ranking official of the Seleucid king around 180 BC who was sent to seize the wealth from the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. Heliodorus’s confiscation of the money was prevented by a heavenly apparition and served as a demonstration of divine protection over the Jerusalem Temple. King says that the subject and characters in the painting are a transparent representation of Louis’s expulsion from the Italian peninsula. The author further notes that it highlights Raphael’s ready willingness (as opposed to Michelangelo’s strong reluctance) to engage in bald-faced propaganda on behalf of their patron. Raphael would ultimately depict the controversial pope four times in Vatican frescoes.

Against all precedent and canonical law, Julius began wearing a beard in 1510 in emulation of his namesake, Julius Ceasar, who grew a beard in 54 BC after learning of the massacre of his forces by the Gauls, swearing not to shave until the death of his men had been avenged. Julius felt the same way about extricating Louis XII and his French army from Italian soil. The pope and his Spanish allies met the French on the battlefield at Ravenna on Easter Sunday 1512. It would prove to be one of the first modern battles in the age of gunpowder-equipped professional armies. The artillery duel and combat lasted three hours; 12,000 soldiers were killed, including 9,000 Spanish. “Ravenna marked an emphatic end to the romantic world of swords and chivalry,” King writes, and it was “a catastrophe of stupendous proportions” for Julius and his allies in the Holy League against France. However, the pope’s prostration would prove to be short-lived. A loyal contingent of 18,000 Swiss soldiers crossed the Alps into Italy at roughly the same time that Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian recalled 9,000 soldiers from their service with the French army in Italy. At a stroke, the crushing defeat of Ravenna was reversed, which King calls “one of the most breathtaking reversals in military history.”

The Sistine Chapel was finally completed and a modicum of peace had come to Italy, even if only briefly. “Never before, in either marble or paint, had the expressive possibilities of the human form been detailed with astonishing invention and aplomb.” King says. But it wasn’t easy. “If Michelangelo was wretched and unhappy by nature,” King writes, “his work in the Sistine Chapel made him all the more miserable.” The great artist lived another 51 years after completing the Sistine Chapel. Raphael succeeded Bramante as architect-in-chief of St Peter’s Basilica in 1514, but then died in 1520 at the age of 37. Michelangelo took over the project in 1547 and remained the chief architect until his death in 1564 at the ripe old age of 89. During this time, he made significant changes to the design, most notably simplifying Bramante’s original plan and focusing on the central dome, which became one of his most famous architectural achievements. Meanwhile, he labored more than 30 years on a scaled back version of Julius’s tomb, which was completed in 1545, and is located in the Basilica of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, walked past obviously by millions of tourists each year on their way to the Colosseum.

Leave a comment