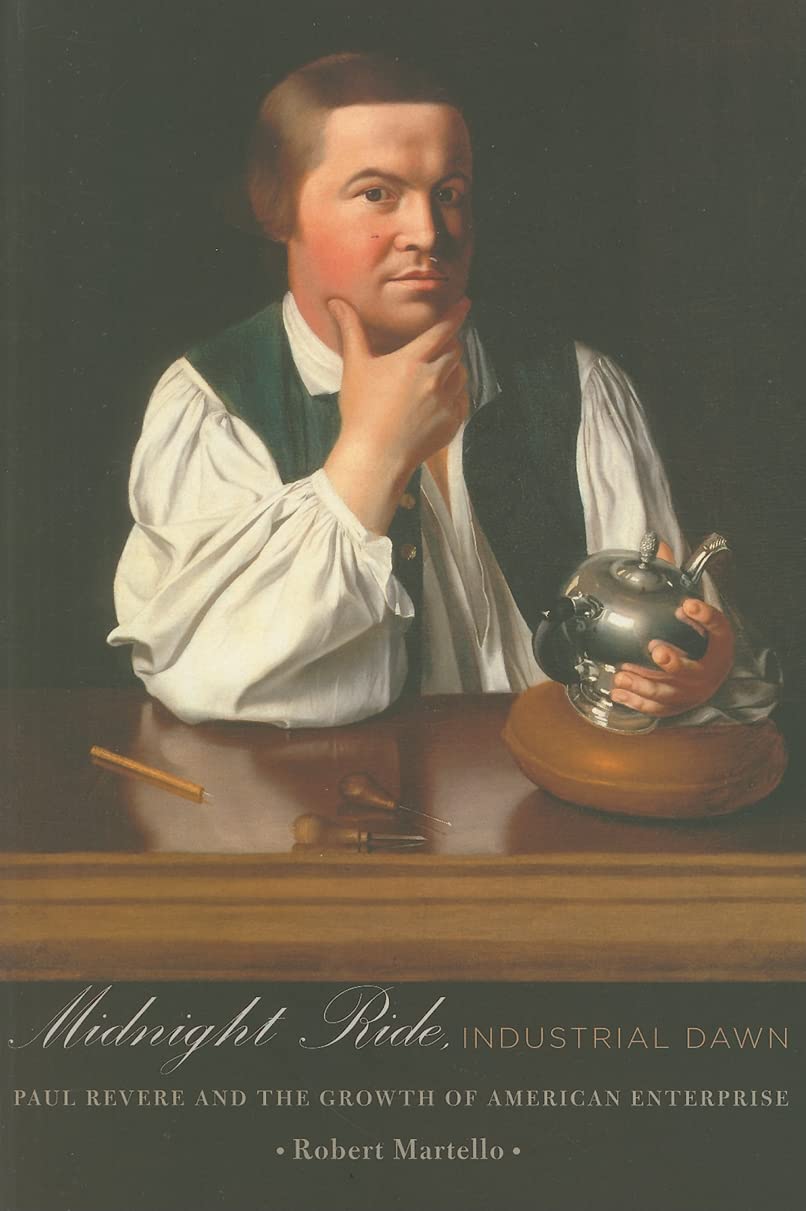

“Listen, my children, and you shall hear, Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.” So begins one of the most famous poems in American history, “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1860). Published forty-two years after the death of the great American patriot, Longfellow’s poem cemented Paul Revere’s name in American history. In the book “Midnight Ride, Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American Enterprise” (2010), historian of technology Robert Martello argues that artisan craftsman Revere played a much bigger and more strategic role in American history for a very different reason – the development of American capital industrialism and, ultimately, mass production.

The main theme of this book is that Paul Revere played a pivotal role in both the American and Industrial Revolutions, and it was his role in the latter that was more important. “Revere became one of the first Americans to shift from the role of a skilled artisan-laborer into the new one of a manufactory owner-manager,” Martello writes. Revere ultimately occupied a middle ground between the “art and mystery” world of the artisan craftsman and full-scale mass producing industrial capitalism that the author calls “proto-industrialism,” a clumsy and temporary but effective mashup of the best parts of the old world and the new.

Revere was born in Boston in 1734. His father was a first-generation French Huguenot immigrant and silversmith named Apollos Rivoire. Rivoire arrived in Boston around 1716 and apprenticed under John Coney, the finest and most renowned silversmith of his day. The tremendous reputational and artistic strengths of Coney eventually paid handsome dividends for Paul Revere who gained wealthy clients simply because of his craft lineage stretching back to the great silversmith through his father. Martello says that Revere epitomized the capitalist mindset and was one of the first artisanal craftsmen to adopt double-entry bookkeeping, wage labor, and diversification into new product lines and business endeavors. Rivoire died in 1754 when Revere was just nineteen years old. As the oldest male in the family he was thrust into a leadership position and forced to take over his father’s thriving silver shop. Thus, Revere vaulted over the traditional journeyman stage of craft advancement and went straight from apprentice to master with a fully-equipped shop of his own. He quickly established himself in the Boston craft community as a man of remarkable talent and versatility. He married twice and fathered sixteen children (only five of whom outlived him) and left fifty-one grandchildren.

By the time of the American Revolution, craftsmen probably made up ten to twenty percent of the population. Colonial society was strictly hierarchical. At the top were the wealthy gentlemen gentry – the large landowners, merchants, and lawyers who made up the political leadership class. In 1771 this top ten percent of Boston society owned two-thirds of the wealth. Revere was acutely aware of social class and hierarchy. He dreamed of joining this upper echelon of society who were marked by a combination of their education, wealth, manners, virtue, and personal honor, as well as what they didn’t do, namely engage in manual labor. Revere strove after it all his life and never quite made it.

Rather, Revere languished at the pinnacle of the craft pyramid, which included trades like printing, silversmithing, and clockmaking, all of which required a great range of skills and high capital requirements for a wide variety of expensive tools. The middle layer of the craft hierarchy included fields like blacksmithing and carpentry, which still required significant skill, risk, and expensive tools and raw materials. At the bottom of the pyramid were the trades with the lowest startup costs and shortest apprenticeships, such as tailoring, shoemaking, and candlemaking.

Martello says that a colonial silversmith’s reputation was based on a combination of factors: his mentor, his technical and artistic skill, the social respectability and loyalty of his client list, and integrity. Revere boasted high marks in all categories. By 1775 he was one of the most versatile and reputable silversmiths in Boston. In the years before the Revolution he averaged an annual income of 85 pounds at a time when a journeyman silversmith might earn 45 pounds and a free white laborer just 12 pounds. Records show that Revere had at least 750 known patrons, many of them were members of the various civic organizations that Revere participated in (a full one-third of his clients were freemasons). Roughly twenty percent of Bostonians owned some silver objects, mostly flatware. Only the top five percent owned numerous pieces of silver, such as tea sets. Revere’s meticulous recordkeeping shows that he produced 1,145 silver items before the war (1761 to 1775). His production skyrocketed after the war when he introduced silver rolling machinery. Revere finished 4,210 objects before moving more full time into metalworking (1779 to 1797), with half of his production coming in flatware (spoons and buckles mostly), although Revere still dominated Boston’s teapot market, producing 38 after the war while the two other leading silversmiths made five combined.

Paul Revere actively and passionately supported the resistance movement to British colonialism and mercantilism from start to finish. According to a letter Revere wrote in 1782, King George III and ministers “do not want colonies of free men they wanted colonies of Slaves.” Revere took meaningful leadership positions in virtually every organization he joined in Boston, but his societal and intellectual credentials barred him from taking a role among the highest ranks of the Patriot movement. He took public service quite seriously. Revere’s facility with new technology and processes helped to quickly develop a gunpowder mill in Stoughton, Massachusetts that began operation in 1776, but his main role within the Sons of Liberty was that of primary message courier. He remained silent on the details of his Midnight Ride for the rest of his life. Revere sought an officer’s commission in the Continental Army, but was denied. He later served as an artillery major in the Massachusetts milita’s first regiment. He participated in an assault on a British fort on Penobscot Bay in Maine in July 1779. It was the largest naval expedition of the Revolutionary War and ended in total disaster. Revere was court-martialed and dishonorably discharged. Martello says it was Revere’s “greatest defeat” and seriously jeopardized his chances of ever being accepted into the gentry, even after the departure of eighty thousand Loyalists left gaping holes at the highest levels of the social and economic ladder.

After the war Revere dedicated his efforts to achieving the lofty status of merchant, all in the hopes of climbing out of the middle-class and into the social rank of gentlemen with the title “Paul Revere, Esquire.” “He wanted to become a gentleman,” Martello writes, “to have influence, and to serve society in a meaningful manner.” A massive glut of goods, collapse in credit, and the scarcity of specie currency after the war led to a prolonged economic recession in the 1780s. By 1781 the government had issued $400 million in paper currency, which were trading at $167 to $1 in specie. Simply put, the macroeconomic environment undermined Revere’s best efforts.

“Emulation was the essence of [Revere’s] genius,” Martello writes. He used this genius to establish himself in metalworking. He started by purchasing a rolling mill in the mid-1780s to roll silver. It was the first step in his journey away from the world of the skilled craftsman and toward that of the machine – a specialized, complex, multicomponent device that strives to produce standardized output. Martello argues that the shift from tools to machines foreshadowed the arrival of industrial capitalism. “Revere’s combination of rolling technology and construction methods allowed him to increase output, maintain quality, lower production costs, and decrease his own involvement in the shop.” So too did the rise of wage labor as Revere consistently embraced the most promising new technology and methods of production while maintaining the most reliable of the old ones. By the early nineteenth century the hierarchical age of the artisan craftsman with a clearly defined ladder of apprentice, journeyman, and master had come to an end. A nebulous middle ground of “proto-industry” was quickly giving way to industrial capitalism.

Great Britain had the things the infant United States needed to grow and succeed – namely capital and technological expertise – but they guarded their resources and advantages jealously. America remained highly vulnerable to retraction of British capital and the dumping of cheap British goods. In 1787, at the age of 52, Revere ventured into the iron-casting business, one of the technical capacities the new Republic lacked. Martello says that moving into the metalworking industry offered Revere three things he valued above all else: income, prestige, and entryway to the upper echelon of society and political leadership. The American colonies excelled at producing pig and bar iron. At the time of the outbreak of the Revolution, America produced fifteen percent of the world’s output, making it the third largest iron-producing nation. But the Iron Act of 1750, while encouraging duty free export of iron back to Britain, forbade all import of advanced processing works, such as rolling mills and plating. The United States sought to close the technology gap with the Old World by aggressively seeking technology transfer and the immigration of skilled workers, especially from Britain, which Parliament sought to prevent with a law passed in 1785 closing off the export of ironmaking tools and the poaching of skilled labor.

Blast furnaces represented one of the earliest forms of large-scale business in America, often employing over a dozen men. Revere started out with a foundry, which shapes metal rather than makes it like a blast furnace. By 1793 Revere’s foundry generated 393 pounds in sales against 311 pounds in expense for a profit of 82 pounds and a gross margin of roughly twenty percent. “Revere’s rapid foundry success resulted from fortuitous timing, innate technical aptitude, thorough research, and the casting experience he gained from silverworking.” He also took his first confident steps in the direction of mass production by producing uniform metal and standardized objects.

In 1792 Revere took a decisive step in marrying his business acumen with his desire to serve society and his religion when he entered the bell-making market, which also introduced him to the challenges of working with copper. One of his greatest and most consistent challenges was raw material acquisition as Britain dominated the raw copper market. Over three-quarters of his total operating expenses for his furnace between 1799 and 1801 was for copper. Moreover, unlike iron, copper smelting must remove all impurities before it can be worked. Bell-making, which came in three varieties and sizes (ship, school, and church), was a high tech trade of the period. Martello calls it “one of the most complex and unforgiving processes practised in eighteenth century America.” Bells were made from bronze, which is created by combining roughly 75 percent copper with 25 percent tin (although Revere’s formula nudged the copper component up to 77 percent). Each bell had its own unique sound. Between 1792 and 1810 (the year he retired), Revere’s shop produced 103 bells with an average weight of 825 pounds.

In 1794 Revere entered the cutting-edge field of cannon casting, “the quickest and easiest technological leap of Revere’s lifetime,” Martello says. The metals and equipment were virtually the same as bell-making, only “gunmetal” is 90 percent copper and 10 percent tin. Almost immediately the federal government hired him to cast ten howitzers, introducing Revere to a high profile client that would dominate the rest of his career. Artillery production boosted Revere’s income, reputation, and metallurgical competence. His shop would produce almost 100 howitzers and cannons for the federal government and state militias between 1794 and 1800.

Next, leveraging his federal contracts and contacts, Revere segued into the production of malleable copper parts, mainly the mass production of copper bolts, spikes, and other fasteners for US naval vessels that required rust-proof metal. Revere would provide over 8,000 pounds of brass fittings for the construction of the USS Constitution (“Old Ironsides”). His profit margins were consistently around twenty percent. This also represented Revere’s first major foray into low-cost, high-volume production since his work in silver flatware. By the turn of the nineteenth century “Revere’s achievements truly separated him from most if not all American metalworkers,” Martello says.

The culmination of Revere’s climb up the technological ladder came in 1798 with his entry into the highly lucrative and highly elusive practice of copper rolling, which was critical for sheathing the hulls of military and commercial trading ships to prevent the fast and costly growth of “sea mat” (i.e. barnacle growth) and destructive shipworms. The first ship to receive copper hull sheathing was the HMS Alarm in 1758; by 1781 the entire British fleet was sheathed. The price of copper doubled during the 1790s from 25 cents per pound to 50. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the United States was completely inexperienced in copper rolling; it presented a significant national security threat. Benjamin Stoddert, secretary of the navy under President John Adams, played a major role in Revere’s later career and ultimate success. Stoddert was a “Federalist to the core,” Martello says, and pushed aggressively for the expansion of the United States Navy, which was re-established in 1794 after being disbanded after the American Revolution. Stoddert strove to make the Navy more modern and self-sufficient. Martello claims Stoddert’s work was a smashing success. Within one year of the first new frigates hitting the water shipping insurance rates dropped so much as to cover the entire cost of building the fleet. “Stoddert’s interest in naval self-sufficiency had permanent ramifications for the future of copperworking in America,” the author says.

Copper represented fifteen percent of the total construction cost of the US Navy’s first six frigates. Stoddert estimated $170,000 in copper expenses, over half of which would be used for sheathing. The navy secretary was willing to front $10,000 (roughly $185,000 in today’s dollars) in the form of a government loan in 1800 to help jumpstart the American copper industry. Revere jumped at the opportunity and used the money to establish a water-powered copper mill about 15 miles outside of Boston on the Neponset River in Canton, which ended up costing him $15,000. Stoddert was dismissed from office in March 1801 after Jefferson’s Revolution of 1800. “Jefferson’s succession to the presidency immediately shattered Stoddert’s long-term naval plans,” Martello says, “with dire consequences for manufacturers such as Revere.” Naval appropriations shriveled from $3 million in 1800 to $1 million in 1802 and kept falling till 1805. Nevertheless, government loans and guaranteed contracts delivered by Stoddert were necessary for Revere’s ability to get up and running in copper rolling. He would eventually branch out into providing copper boiler liners for Robert Fulton’s steamships, sheathing for the copper dome of New York’s City Hall, and copper cookware, which lives on to this day in the brand Revere Ware. Between 1804 and 1807 Revere’s profit margin on sheet copper reached 32 percent on revenues of over $10,000, a remarkable achievement when one considers the raw material scarcity and labor and capital shortages that plagued the early republic.

Unlike the distant and secretive British, Revere freely shared his experiences, lessons, and knowledge with fellow manufacturers. This openness contributed to the accelerating shift from the colonial mercantile system to a market economy that promoted capitalist attitudes and industrialization. “The early republic period was the era of capitalist transformation,” Martello says. By the 1820s national progress began to be associated with technological advancement, a trend that rapidly accelerated with the growth of railroads before the Civil War.

Paul Revere retired in 1811 at age 76 and died in 1819. He was a true American industrial pioneer and, according to Martello, “the most accomplished metallurgist in America.” The author says that Revere was the vanguard of the emerging industrial and managerial revolutions, especially his use of advanced bookkeeping methods. More importantly, he led the transition of manufacturing in the direction of what has been called the “American system” – a precursor to mass production that focused on the cheap, large-scale production of standardized output, such as Revere’s bell manufacturing based on consistent procedures and a small number of reusable molds. (The efficiency of standardization was reflected in the prices Revere charged: 42 cents per pound for bells, 50 cents for bolts and spikes, and 55 cents for cannon.) Revere’s son, Joseph Warren Revere, took over Revere and Son and ran it efficiently until his death in 1868 at age 91. Six copper companies merged in 1928 to create Revere Copper & Brass.

Leave a comment